New documents and court records obtained by EFF show that Texas deputies queried Flock Safety's surveillance data in an abortion investigation, contradicting the narrative promoted by the company and the Johnson County Sheriff that she was “being searched for as a missing person,” and that “it was about her safety.”

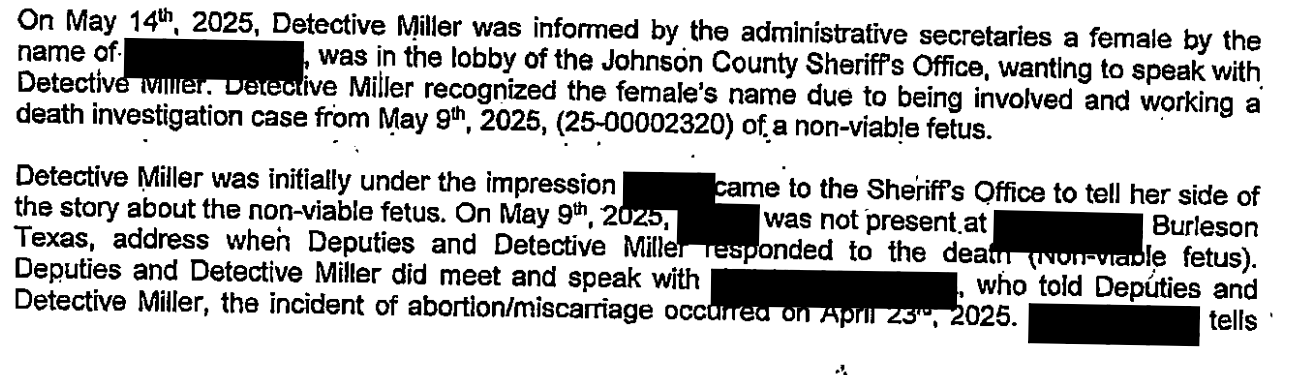

The new information shows that deputies had initiated a "death investigation" of a "non-viable fetus," logged evidence of a woman’s self-managed abortion, and consulted prosecutors about possibly charging her.

Johnson County Sheriff Adam King repeatedly denied the automated license plate reader (ALPR) search was related to enforcing Texas's abortion ban, and Flock Safety called media accounts "false," "misleading" and "clickbait." However, according to a sworn affidavit by the lead detective, the case was in fact a death investigation in response to a report of an abortion, and deputies collected documentation of the abortion from the "reporting person," her alleged romantic partner. The death investigation remained open for weeks, with detectives interviewing the woman and reviewing her text messages about the abortion.

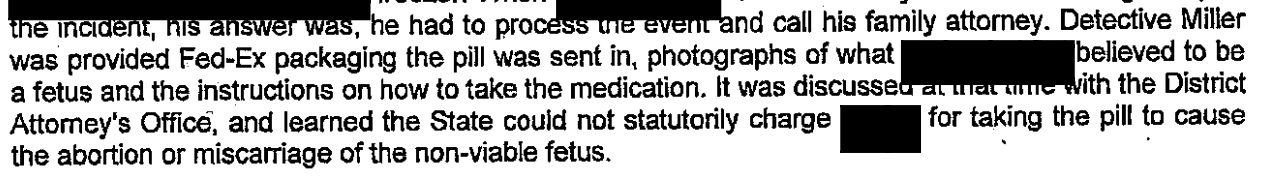

The documents show that the Johnson County District Attorney's Office informed deputies that "the State could not statutorily charge [her] for taking the pill to cause the abortion or miscarriage of the non-viable fetus."

An excerpt from the JCSO detective's sworn affidavit.

A False Narrative Emerges

Last May, 404 Media obtained data revealing the Johnson County Sheriff’s Office conducted a nationwide search of more than 83,000 Flock ALPR cameras, giving the reason in the search log: “had an abortion, search for female.” Both the Sheriff's Office and Flock Safety have attempted to downplay the search as akin to a search for a missing person, claiming deputies were only looking for the woman to “check on her welfare” and that officers found a large amount of blood at the scene – a claim now contradicted by the responding investigator’s affidavit. Flock Safety went so far as to assert that journalists and advocates covering the story intentionally misrepresented the facts, describing it as "misreporting" and "clickbait-driven."

As Flock wrote of EFF's previous commentary on this case (bold in original statement):

Earlier this month, there was purposefully misleading reporting that a Texas police officer with the Johnson County Sheriff’s Office used LPR “to target people seeking reproductive healthcare.” This organization is actively perpetuating narratives that have been proven false, even after the record has been corrected.

According to the Sheriff in Johnson County himself, this claim is unequivocally false.

… No charges were ever filed against the woman and she was never under criminal investigation by Johnson County. She was being searched for as a missing person, not as a suspect of a crime.

That sheriff has since been arrested and indicted on felony counts in an unrelated sexual harassment and whistleblower retaliation case. He has also been charged with aggravated perjury for allegedly lying to a grand jury. EFF filed public records requests with Johnson County to obtain a more definitive account of events.

The newly released incident report and affidavit unequivocally describe the case as a "death investigation" of a "non-viable fetus." These documents also undermine the claim that the ALPR search was in response to a medical emergency, since, in fact, the abortion had occurred more than two weeks before deputies were called to investigate.

In recent years, anti-abortion advocates and prosecutors have increasingly attempted to use “fetal homicide” and “wrongful death” statutes – originally intended to protect pregnant people from violence – to criminalize abortion and pregnancy loss. These laws, which exist in dozens of states, establish legal personhood of fetuses and can be weaponized against people who end their own pregnancies or experience a miscarriage.

In fact, a new report from Pregnancy Justice found that in just the first two years since the Supreme Court’s decision in Dobbs, prosecutors initiated at least 412 cases charging pregnant people with crimes related to pregnancy, pregnancy loss, or birth–most under child neglect, endangerment, or abuse laws that were never intended to target pregnant people. Nine cases included allegations around individuals’ abortions, such as possession of abortion medication or attempts to obtain an abortion–instances just like this one. The report also highlights how, in many instances, prosecutors use tangentially related criminal charges to punish people for abortion, even when abortion itself is not illegal.

By framing their investigation of a self-administered abortion as a “death investigation” of a “non-viable fetus,” Texas law enforcement was signaling their intent to treat the woman’s self-managed abortion as a potential homicide, even though Texas law does not allow criminal charges to be brought against an individual for self-managing their own abortion.

The Investigator's Sworn Account

Over two days in April, the woman went through the process of taking medication to induce an abortion. Two weeks later, her partner–who would later be charged with domestic violence against her–reported her to the sheriff's office.

The documents confirm that the woman was not present at the home when the deputies “responded to the death (Non-viable fetus).” As part of the investigation, officers collected evidence that the man had assembled of the self-managed abortion, including photographs, the FedEx envelope the medication arrived in, and the instructions for self-administering the medication.

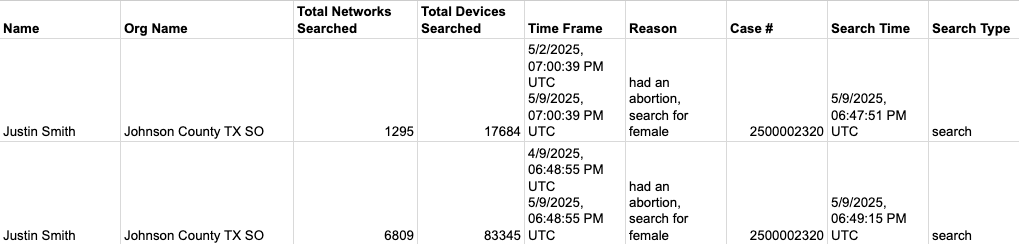

Another Johnson County official ran two searches through the ALPR database with the note "had an abortion, search for female," according to Flock Safety search logs obtained by EFF. The first search, which has not been previously reported, probed 1,295 Flock Safety networks–composed of 17,684 different cameras–going back one week. The second search, which was originally exposed by 404 Media, was expanded to a full month of data across 6,809 networks, including 83,345 cameras. Both searches listed the same case number that appears on the death investigation/incident report obtained by EFF.

After collecting the evidence from the woman’s partner, the investigators say they consulted the district attorney’s office, only to be told they could not press charges against the woman.

An excerpt from the JCSO detective's sworn affidavit.

Only after all that did they learn that she actually wanted to report a violent assault by her partner–the same individual who had called the police to report her abortion. She alleged that less than an hour after the abortion, he choked her, put a gun to her head, and made her beg for her life. The man was ultimately charged in connection with the assault, and the case is ongoing.

This documented account runs completely counter to what law enforcement and Flock have said publicly about the case.

Johnson County Sheriff Adam King told 404 media: "Her family was worried that she was going to bleed to death, and we were trying to find her to get her to a hospital.” He later told the Dallas Morning News: “We were just trying to check on her welfare and get her to the doctor if needed, or to the hospital."

The account by the detective on the scene makes no mention of concerned family members or a medical investigator. To the contrary, the affidavit says that they questioned the man as to why he "waited so long to report the incident," and he responded that he needed to "process the event and call his family attorney." The ALPR search was recorded 2.5 hours after the initial call came in, as documented in the investigation report.

The Desk Sergeant's Report—One Month Later

EFF obtained a separate "case supplemental report" written by the sergeant who says he ran the May 9 ALPR searches.

The sergeant was not present at the scene, and his account was written belatedly on June 5, almost a month after the incident and nearly a week after 404 Media had already published the sheriff’s alternative account of the Flock Safety search, kicking off a national controversy. The sheriff's office provided this sergeant's report to Dallas Morning News.

In the report, the sergeant claims that the officers on the ground asked him to start "looking up" the woman due to there being "a large amount of blood" found at the residence—an unsubstantiated claim that is in conflict with the lead investigator’s affidavit. The sergeant repeatedly expresses that the situation was "not making sense." He claims he was worried that the partner had hurt the woman and her children, so "to check their welfare," he used TransUnion's TLO commercial investigative database system to look up her address. Once he identified her vehicle, he ran the plate through the Flock database, returning hits in Dallas.

Two abortion-related searches in the JCSO's Flock Safety ALPR audit log

It's also unclear why the sergeant submitted the supplemental report at all, weeks after the incident. By that time, the lead investigator had already filed a sworn affidavit that contradicted the sergeant's account. For example, the investigator, who was on the scene, does not describe finding any blood or taking blood samples into evidence, only photographs of what the partner believed to be the fetus.

One area where they concur: both reports are clearly marked as a "death investigation."

Correcting the Record

Since 404 Media first reported on this case, King has perpetuated the false narrative, telling reporters that the woman was never under investigation, that officers had not considered charges against her, and that "it was all about her safety."

But here are the facts:

- The reports that have been released so far describe this as a death investigation.

- The lead detective described himself as "working a death investigation… of a non-viable fetus" at the time he interviewed the woman (a week after the ALPR searches).

- The detective wrote that they consulted the district attorney's office about whether they could charge her for "taking the pill to cause the abortion or miscarriage of the non-viable fetus." They were told they could not.

- Investigators collected a lot of data, including photos and documentation of the abortion, and ran her through multiple databases. They even reviewed her text messages about the abortion.

- The death investigation was open for more than a month.

The death investigation was only marked closed in mid-June, weeks after 404 Media's article and a mere days before the Dallas Morning News published its report, in which the sheriff inaccurately claimed the woman "was not under investigation at any point."

Flock has promoted this unsupported narrative on its blog and in multimedia appearances. We did not reach out to Flock for comment on this article, as their communications director previously told us the company will not answer our inquiries until we "correct the record and admit to your audience that you purposefully spread misinformation which you know to be untrue" about this case.

Consider the record corrected: It turns out the truth is even more damning than initially reported.

The Aftermath

In the aftermath of the original reporting, government officials began to take action. The networks searched by Johnson County included cameras in Illinois and Washington state, both states where abortion access is protected by law. Since then:

- The Illinois Secretary of State has announced his intent to “crack down on unlawful use of license plate reader data,” and urged the state’s Attorney General to investigate the matter.

- In California, which also has prohibitions on sharing ALPR out of state and for abortion-ban enforcement, the legislature cited the case in support of pending legislation to restrict ALPR use.

- Ranking Members of the House Oversight Committee and one of its subcommittees launched a formal investigation into Flock’s role in “enabling invasive surveillance practices that threaten the privacy, safety, and civil liberties of women, immigrants, and other vulnerable Americans.”

- Senator Ron Wyden secured a commitment from Flock to protect Oregonians' data from out-of-state immigration and abortion-related queries.

In response to mounting pressure, Flock announced a series of new features supposedly designed to prevent future abuses. These include blocking “impermissible” searches, requiring that all searches include a “reason,” and implementing AI-driven audit alerts to flag suspicious activity. But as we've detailed elsewhere, these measures are cosmetic at best—easily circumvented by officers using vague search terms or reusing legitimate case numbers. The fundamental architecture that enabled the abuse remains unchanged.

Meanwhile, as the news continued to harm the company's sales, Flock CEO Garrett Langley embarked on a press tour to smear reporters and others who had raised alarms about the usage. In an interview with Forbes, he even doubled down and extolled the use of the ALPR in this case.

So when I look at this, I go “this is everything’s working as it should be.” A family was concerned for a family member. They used Flock to help find her, when she could have been unwell. She was physically okay, which is great. But due to the political climate, this was really good clickbait.

Nothing about this is working as it should, but it is working as Flock designed.

The Danger of Unchecked Surveillance

Flock Safety ALPR cameras

The searches in this case may have violated laws in states like Washington and Illinois, where restrictions exist specifically to prevent this kind of surveillance overreach. But those protections mean nothing when a Texas deputy can access cameras in those states with a few keystrokes, without external review that the search is legal and legitimate under local law. In this case, external agencies should have seen the word "abortion" and questioned the search, but the next time an officer is investigating such a case, they may use a more vague or misleading term to justify the search. In fact, it's possible it has already happened.

ALPRs were marketed to the public as tools to find stolen cars and locate missing persons. Instead, they've become a dragnet that allows law enforcement to track anyone, anywhere, for any reason—including investigating people's healthcare decisions. This case makes clear that neither the companies profiting from this technology nor the agencies deploying it can be trusted to tell the full story about how it's being used.

States must ban law enforcement from using ALPRs to investigate healthcare decisions and prohibit sharing data across state lines. Local governments may try remedies like reducing data retention period to minutes instead of weeks or months—but, really, ending their ALPR programs altogether is the strongest way to protect their most vulnerable constituents. Without these safeguards, every license plate scan becomes a potential weapon against a person seeking healthcare.