At EFF we spend a lot of time thinking about Street Level Surveillance technologies—the technologies used by police and other authorities to spy on you while you are going about your everyday life—such as automated license plate readers, facial recognition, surveillance camera networks, and cell-site simulators (CSS). Rayhunter is a new open source tool we’ve created that runs off an affordable mobile hotspot that we hope empowers everyone, regardless of technical skill, to help search out CSS around the world.

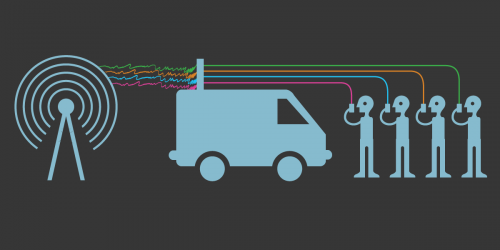

CSS (also known as Stingrays or IMSI catchers) are devices that masquerade as legitimate cell-phone towers, tricking phones within a certain radius into connecting to the device rather than a tower.

CSS operate by conducting a general search of all cell phones within the device’s radius. Law enforcement use CSS to pinpoint the location of phones often with greater accuracy than other techniques such as cell site location information (CSLI) and without needing to involve the phone company at all. CSS can also log International Mobile Subscriber Identifiers (IMSI numbers) unique to each SIM card, or hardware serial numbers (IMEIs) of all of the mobile devices within a given area. Some CSS may have advanced features allowing law enforcement to intercept communications in some circumstances.

What makes CSS especially interesting, as compared to other street level surveillance, is that so little is known about how commercial CSS work. We don’t fully know what capabilities they have or what exploits in the phone network they take advantage of to ensnare and spy on our phones, though we have some ideas.

We also know very little about how cell-site simulators are deployed in the US and around the world. There is no strong evidence either way about whether CSS are commonly being used in the US to spy on First Amendment protected activities such as protests, communication between journalists and sources, or religious gatherings. There is some evidence—much of it circumstantial—that CSS have been used in the US to spy on protests. There is also evidence that CSS are used somewhat extensively by US law enforcement, spyware operators, and scammers. We know even less about how CSS are being used in other countries, though it's a safe bet that in other countries CSS are also used by law enforcement.

Much of these gaps in our knowledge are due to a lack of solid, empirical evidence about the function and usage of these devices. Police departments are resistant to releasing logs of their use, even when they are kept. The companies that manufacture CSS are unwilling to divulge details of how they work.

Until now, to detect the presence of CSS, researchers and users have had to either rely on Android apps on rooted phones, or sophisticated and expensive software-defined radio rigs. Previous solutions have also focused on attacks on the legacy 2G cellular network, which is almost entirely shut down in the U.S. Seeking to learn from and improve on previous techniques for CSS detection we have developed a better, cheaper alternative that works natively on the modern 4G network.

Introducing Rayhunter

To fill these gaps in our knowledge, we have created an open source project called Rayhunter.1 It is developed to run on an Orbic mobile hotspot (Amazon, Ebay) which is available for $20 or less at the time of this writing. We have tried to make Rayhunter as easy as possible to install and use, regardless of your level of technical knowledge. We hope that activists, journalists, and others will run these devices all over the world and help us collect data about the usage and capabilities of cell-site simulators (please see our legal disclaimer.)

Rayhunter works by intercepting, storing, and analyzing the control traffic (but not user traffic, such as web requests) between the mobile hotspot Rayhunter runs on and the cell tower to which it’s connected. Rayhunter analyzes the traffic in real-time and looks for suspicious events, which could include unusual requests like the base station (cell tower) trying to downgrade your connection to 2G which is vulnerable to further attacks, or the base station requesting your IMSI under suspicious circumstances.

Rayhunter notifies the user when something suspicious happens and makes it easy to access those logs for further review, allowing users to take appropriate action to protect themselves, such as turning off their phone and advising other people in the area to do the same. The user can also download the logs (in PCAP format) to send to an expert for further review.

The default Rayhunter user interface is very simple: a green (or blue in colorblind mode) line at the top of the screen lets the user know that Rayhunter is running and nothing suspicious has occurred. If that line turns red, it means that Rayhunter has logged a suspicious event. When that happens the user can connect to the device's WiFi access point and check a web interface to find out more information or download the logs.

Rayhunter in action

Installing Rayhunter is relatively simple. After buying the necessary hardware, you’ll need to download the latest release package, unzip the file, plug the device into your computer, and then run an install script for either Mac or Linux (we do not support Windows as an installation platform at this time.)

We have a few different goals with this project. An overarching goal is to determine conclusively if CSS are used to surveil free expression such as protests or religious gatherings, and if so, how often it’s occurring. We’d like to collect empirical data (through network traffic captures, i.e. PCAPs) about what exploits CSS are actually using in the wild so the community of cellular security researchers can build better defenses. We also hope to get a clearer picture of the extent of CSS usage outside of the U.S., especially in countries that do not have legally enshrined free speech protections.

Once we have gathered this data, we hope we can help folks more accurately engage in threat modeling about the risks of cell-site simulators, and avoid the fear, uncertainty, and doubt that comes from a lack of knowledge. We hope that any data we do find will be useful to those who are fighting through legal process or legislative policy to rein in CSS use where they live.

If you’re interested in running Rayhunter for yourself, pick up an Orbic hotspot (Amazon, Ebay), install Rayhunter, check out the project's Frequently Asked Questions, and help us collect data about how IMSI catchers operate! Together we can find out how cell site simulators are being used, and protect ourselves and our communities from this form of surveillance.

—

Legal disclaimer: Use Rayhunter at your own risk. We believe running this program does not currently violate any laws or regulations in the United States. However, we are not responsible for civil or criminal liability resulting from the use of this software. If you are located outside of the US please consult with an attorney in your country to help you assess the legal risks of running this program

- 1. A note on the name: Rayhunter is named such because Stingray is a brand name for cell-site simulators which has become a common term for the technology. One of the only natural predators of the stingray in the wild is the orca, some of which hunt stingrays for pleasure using a technique called wavehunting. Because we like Orcas, we don’t like stingray technology (though the animals are great!), and because it was the only name not already trademarked, we chose Rayhunter.