In their effort to prevent states from protecting a free and open Internet, a small handful of massive and extraordinarily profitably Internet service providers (ISPs) are telling state legislatures that network neutrality would hinder their ability to raise revenues to pay for upgrades and thus force them to charge consumers higher bills for Internet access. This is because state-based network neutrality will prohibit data discrimination schemes known as “paid prioritization” where the ISP charges websites and applications new tolls and relegate those that do not pay to the slow lane.

In essence, they are saying they have to charge new fees to websites and applications in order to pay for upgrades and maintenance to their networks. In other words, people are using so much of their broadband product that they can’t keep up on our monthly subscriptions.

Nothing could be further from the truth.

Today in America we have ISPs that are already deploying 21st-century high-speed broadband without resorting to violating network neutrality or monetizing our personal information with advertisers. The fact is nothing—and certainly not a lack of funds—prevents incumbents from upgrading their networks and bringing a vast majority of American cities they serve into the 21st century of Internet access. That means gigabit broadband services anywhere between $40 to $70 a month (the range people in the handful of competitive markets pay today). Yet, year after year, these ISPs have pocketed billions in profits and it is not until they face competition from a rival provider that they upgrade their networks.

Ultimately, it’s not network neutrality that prevents the large ISPs from upgrading their networks while lowering prices. It is a lack of incentive.

The Biggest Cost For An ISP is the Initial Deployment, Not Internet Usage

ISPs misrepresent to policymakers the true cost drivers of broadband deployment as a way to stave off pro-consumer protections. In fact, the biggest cost barrier for an ISP’s creation is the initial construction of the network (as opposed to its future upgrades) and the civil works that entails. That is what the Google Fiber deployment has taught us and that is what studies in the European Union concluded when analyzing how to improve the market entry prospects of ISPs.

Some estimates suggest the cost of deployment can be close to 80 percent of the entire cost portfolio of an ISP. Note that means operations and maintenance of the network (that includes all of the broadband usages of its customers) could be as little as 20% of the ISP’s costs. This is acutely true when it comes to a fiber to the home deployment where the infrastructure (fiber optic cable) is effectively future-proof and can be upgraded cheaply with advances in electronics.

It is worth remembering that our current incumbent telephone and cable companies have made back their initial investment costs because they entered the market as monopolies in the old days and likely enjoyed favorable financing as safe bets (nothing is safer to invest in than a monopoly). Our current incumbents enjoyed a litany of advantages for being the first to deploy. For example, many buildings as they were constructed prospectively required the installation of a telephone and cable line, which in essence gave them virtually a free ride to customers that new entrants will not enjoy.

This is also why it has been very hard to get new competition because they have to navigate the infrastructure deployment and rights-of-way from a very different position. Another example, when Google was deploying its fiber network in Austin, Texas, it needed to run its wires along the telephone pole system. Unfortunately for Google, AT&T owned many of those poles and simply denied them access to build in their entirety. This is a big reason why many small ISPs supported the FCC’s 2015 Open Internet Order because it guaranteed them rights to access infrastructure if it was owned by an incumbent and prohibited by law the conduct AT&T exhibited in Austin, Texas.

The World’s Fastest ISP Adheres to Network Neutrality and Privacy and Still Makes a Profit

In addition to ISPs not needing new huge sums of money to upgrade and operate their networks, we have a case study that shows that adhering to network neutrality principles while also respecting user privacy by not monetizing their personal information doesn’t prevent ISPs from making the money they need to deploy high-speed affordable Internet.

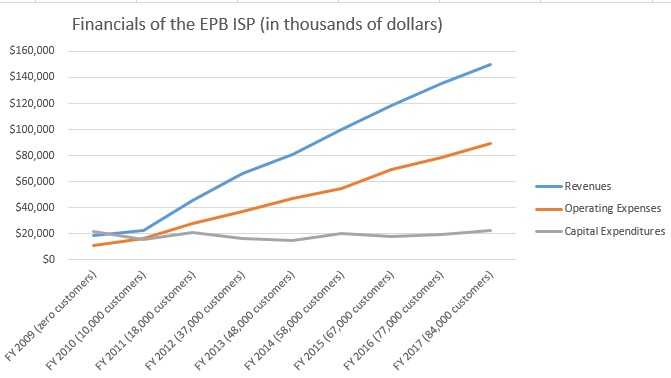

EPB Fiber Optics, a community broadband company run by Chattanooga, Tennessee, offers both gigabit broadband and 10-gigabit broadband as well. A decade of their financial information, including how much they invest, how much the network costs, and how much profit they are making, is available here.

Here is what the data demonstrates in regards to the scalability of fiber optic cable and why ISPs are misleading policymakers when they assert that Internet usage or high bandwidth applications drive their costs.

At the launch of its gigabit broadband service in 2009, EPB started in the red with capital expenditures (money spent on purchasing equipment and improving infrastructure) and operating expenses (maintaining and running the network) far above the revenue. But once they had about 35,000 customers, the network became profitable (all while following network neutrality and not monetizing the personal information of their customers).

In the years that followed, the revenue gained from adding new customers far outpaced their maintenance costs and money spent upgrading their network. It is almost impossible to detect the increased spending EPB underwent to upgrade to a 10-gigabit network in 2016. Often ISPs blame companies like Netflix for driving their costs, yet there is no evidence that increased consumption by the customers of EPB resulted in an increase in their costs that wasn’t already more than compensated by their $50-$70 a month charge. If it was true that high bandwidth applications incurred uniquely high costs to ISPs, then the revenue line would not be outpacing the operating expenses line year after year of growth as online video consumption grew. Those lines would have to be moving closer together.

EPB is able to deploy a 21st Century ISP with the world’s fastest service with just 90,000 customers today while following network neutrality and forgoing extra profits from monetizing personal information like web browsing history. Meanwhile, Comcast sits on about 25 million customers and made $8.6 billion in profits for 2016 (and this was before Congress cut the corporate tax rates). At the same time, both AT&T and Verizon each collected around $13 billion each in profits for 2016.

Charging Low Prices for Huge Amounts of Bandwidth Is Not Exclusively Reserved for Community Broadband

Being able to provide affordable high-speed Internet for a profit while respecting network neutrality and user privacy is something the competitors to the incumbents have repeatedly demonstrated. Take regional provider Sonic for an example and their Brentwood, California deployment where the city’s infrastructure policies eliminated a majority of the costs of building the ISP. Right now Sonic sells gigabit broadband in the city of Brentwood at $40 a month, one of the lowest priced offerings for gigabit service. Again, they are doing this for a profit all while following network neutrality and protecting their customers’ privacy (Sonic regularly supports laws codifying their commitments as well).

The provisioning of the service is not the expensive part of an ISPs business, and the usage of Internet access is not an unsustainable cost driver. If one would to properly diagnose the most efficient way to reduce ISP costs, they would look towards city planning and learn from Brentwood. The Sonic gigabit network all came about because in 1999 the city adopted a building code conduit requirement for all new development. The code required developers to build a 4-inch conduit pipe and then deed it back to the city. The policy goal at the time was to lay infrastructure with the hope of franchising a second cable television provider. However, no new cable company arrived and the city-owned nearly 120 to 150 miles of unused conduit reaching 8,000 homes and commercial zones built since 1999.

In response to the proposal by Sonic to utilize the infrastructure, the city issued a Request for Expression of Interest (RFEI) highlighting the available conduit to the companies Astound, AT&T, Comcast, Google, Level 3, Lit San Leandro, XO Communications, and Sonic. However, the only respondent to the RFEI was Sonic and so the city chose them to deploy the network, which was so lucrative an agreement that Sonic agreed to provide the local schools within the conduit network free gigabit service among other things while still making money.

We Already Pay More Than Enough to Get High-Speed, Affordable Internet Where Our Privacy is Protected and Net Neutrality is Preserved

The fact is, more than half of Americans have one choice for high-speed broadband and the incumbents know they can rest on their legacy investments to maximize profits until they face competition from other broadband providers. They don’t have to make their service better or faster, because most of their customers have to choose between them or nothing. They worked so hard to repeal our privacy protections and repeal net neutrality because since so many of us lack choice in the market they can start increasing their profits and give nothing to the consumer in return.

No regulations banning paid prioritization have prevented them from upgrading their network. We see this in both Chattanooga’s EPB and Brentwood’s Sonic, which operate perfectly well while following network neutrality and have forgoing extra profits from monetizing our personal information.

Net neutrality ensures that ISPs are prevented from harming the competition they face from edge providers (particularly video providers that compete with television such Hulu, Netflix, and Amazon) as well as preserve the innovation benefits an open Internet yields. It also prohibits them from charging unjustified fees on Internet services that will do nothing to improve the Internet but will do real harm to the free and open nature of the network we have enjoyed for decades.