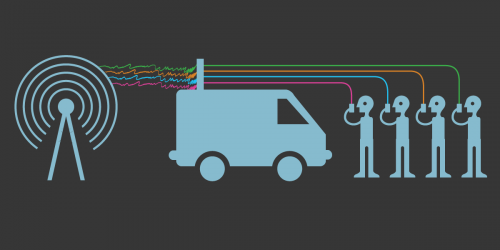

The Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts recently held that officers may not place GPS tracking devices on cars without first getting a warrant. The case, Commonwealth v. Connolly, was decided under the state corollary to the Fourth Amendment, and its reasoning may influence pending GPS tracking cases, including United States v. Jones, where EFF is an amicus.

Connolly decided that the installation of the GPS device was a seizure of the suspect’s vehicle. “When an electronic surveillance device is installed in a motor vehicle, be it a beeper, radio transmitter, or GPS device, the government's control and use of the defendant's vehicle to track its movements interferes with the defendant's interest in the vehicle notwithstanding that he maintains possession of it.” Thus, the court held this interference with the owner’s possessory interest requires a warrant.

Interestingly, Connolly did not hold that it was a violation of the state constitution to use GPS technology to track suspects as they drive. The court merely acknowledged two 1970s era U.S. Supreme Court cases that had found that the Fourth Amendment did not regulate the use of primitive beeper technology that helped officers follow a suspect’s public movements, before moving on to the question of whether the installation was a seizure. Another recent state court case, People v. Weaver in the State of New York, has held that because modern GPS devices are far more powerful than beepers, police must get a warrant to use the trackers, even on cars and people traveling the public roads.

Massachusetts and New York are in the forefront of protecting their citizens’ right to location privacy against technological encroachment. Federal courts should do the same under the Fourth Amendment. For the Constitution to have continued relevance in a technological world, it should protect the privacy that individuals reasonably anticipate as we move through the world, and that means no pervasive, remote, suspicionless, wholesale tracking by GPS or other device.