This is the second part of a three-part series about age verification in the European Union. In this blog post, we take a deep dive into the age verification app solicited by the European Commission, based on digital identities. Part one gives an overview of the political debate around age verification in the EU and part three explores measures to keep all users safe that do not require age checks.

In part one of this series on age verification in the European Union, we gave an overview of the state of the debate in the EU and introduced an age verification app, or mini-wallet, that the European Commission has commissioned. In this post, we will take a more detailed look at the app, how it will work and what some of its shortcomings are.

According to the original tender and the app’s recently published specifications, the Commission is soliciting the creation of a mobile application that will act as a digital wallet by storing a proof of age to enable users to verify their ages and access age-restricted content.

After downloading the app, a user would request proof of their age. For this crucial step, the Commission foresees users relying on a variety of age verification methods, including national eID schemes, physical ID cards, linking the app to another app that contains information about a user’s age, like a banking app, or age assessment through third parties like banks or notaries.

In the next step, the age verification app would generate a proof of age. Once the user would access a website restricting content for certain age cohorts, the platform would request proof of the user’s age through the app. The app would then present proof of the user’s age via the app, allowing online services to verify the age attestation and the user would then access age-restricted websites or content in question. The goal is to build an app that will be aligned and allows for integration with the architecture of the upcoming EU Digital Identity Wallet.

The user journey of the European Commission's age verification app

Review of the Commission’s Specifications for an Age Verification Mini-ID Wallet

According to the specifications for the app, interoperability, privacy and security are key concerns for the Commission in designing the main requirements of the app. It acknowledges that the development of the app is far from finished, but an interactive process, and that key areas require feedback from stakeholders across industry and civil society.

The specifications consider important principles to ensure the security and privacy of users verifying their age through the app, including data minimization, unlinkability (to ensure that only the identifiers required for specific linkable transactions are disclosed), storage limitations, transparency and measures to secure user data and prevent the unauthorized interception of personal data.

However, taking a closer look at the specifications, many of the mechanisms envisioned to protect users’ privacy are not necessary requirements, but optional. For example, the app should implement salted hashes and Zero Knowledge Proofs (ZKPs), but is not required to do so. Indeed, the app’s specifications seem to heavily rely on ZKPs, while simultaneously acknowledging that no compatible ZKP solution is currently available. This warrants a closer inspection of what ZKPs are and why they may not be the final answer to protecting users’ privacy in the context of age verification.

A Closer Look at Zero Knowledge Proofs

Zero Knowledge Proofs provide a cryptographic way to not give something away, like your exact date of birth and age, while proving something about it. They can offer a “yes-or-no” claim (like above or below 18) to a verifier requiring a legal age threshold. Two properties of ZKPs are “soundness” and “zero knowledge.” Soundness is appealing to verifiers and to governments to make it hard for a prover to present forged information. Zero-Knowledge can be beneficial to the holder, because they don’t have to share explicit information, just the proof that said information exists. This is objectively more secure than uploading a picture of your ID to multiple sites or applications, but it still requires an initial ID upload process as mentioned above for activation.

This scheme makes several questionable assumptions. First, that frequently used ZKPs will avoid privacy concerns, and second, that verifiers won’t combine this data with existing information, such as account data, profiles, or interests, for other purposes, such as advertising. The European Commission plans to test this assumption with extremely sensitive data: government-issued IDs. Though ZKPs are a better approach, this is a brand new system affecting millions of people, who will be asked to provide an age proof with potentially higher frequency than ever before. This rolls the dice with the resiliency of these privacy measures over time. Furthermore, not all ZKP systems are the same, and while there is research about its use on mobile devices, this rush to implementation before the research matures puts all of the users at risk.

Who Can Ask for Proof of Your Age?

Regulation on verifiers (the service providers asking for age attestations) and what they can ask for is also just as important to limit a potential flood of verifiers that didn’t previously need age verification. This is especially true for non Know-Your-Customer (KYC) cases, in which service providers are not required to perform due diligence on their users. Equally important are rules that determine the consequences for when verifiers violate those regulations. Up until recently, the eIDAS framework, of which the technical implementation is still being negotiated, required registration certificates across all EU member states for verifiers. By forcing verifiers to register the data categories they intend to ask for, issues like illegal data requests were supposed to be mitigated. But now, this requirement has been rolled back again and the Commission’s planned mini-AV wallet will not require it in the beginning. Users will be asked to prove how old they are without the restraint on verifiers that protects from request abuse. Without verifier accountability, or at least industry-level data categories being given a determined scope, users are being asked to enter into an imbalanced relationship. An earlier mock-up gave some hope for empowered selective disclosure, where a user could toggle giving discrete information on and off during the time of the verifier request. It would be more proactive to provide that setting to the holder in their wallet settings, before a request is made from a relying party.

Privacy tech is offered in this system as a concession to users forced to share information even more frequently, rather than as an additional way to bring equity in existing interactions with those who hold power, through mediating access to information, loans, jobs, and public benefits. Words mean things, and ZKPs are not the solution, but a part of one. Most ZKP systems are more focused on making proof and verification time more efficient than they are concerned with privacy itself. The result of the latest research with digital credentials are more privacy oriented ways to share information. But at this scale, we will need regulation and added measures on aggressive verification to complete the promise of better privacy for eID use.

Who Will Have Access to the Mini-ID Wallet, and Who Will Be Left Out?

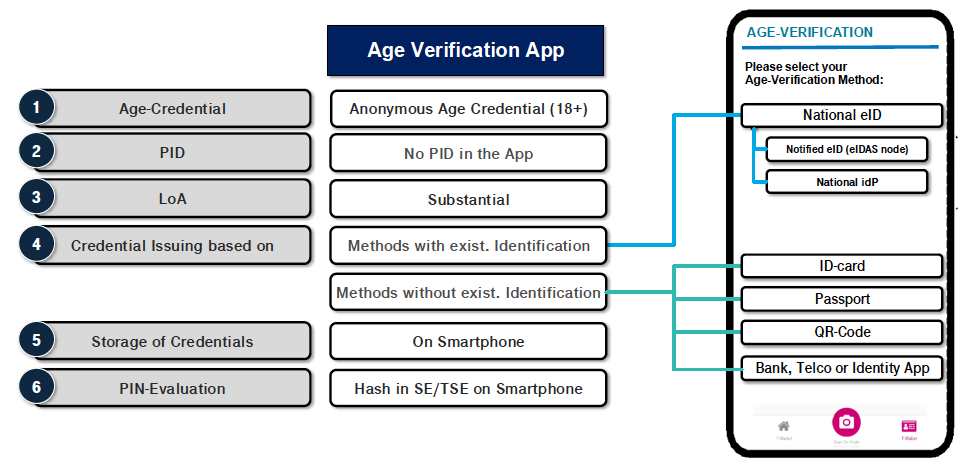

Beyond its technical specifications, the proposed app raises a number of accessibility and participation issues. At its heart, the mini-ID wallet will rely on the verification of a user’s age through a proof of age. According to the tender, the wallet should support four methods for the issuance and proving of age of a user.

Different age verification methods foreseen by the app

The first options are national eID schemes, which is an obvious choice: Many Member States are currently working on (or have already notified) national eID schemes in the context of the eIDAS, Europe’s eID framework. The goal is to allow the mini-ID wallet to integrate with the eIDAS node operated by the European Commission to verify a user’s age. Although many Member States are working on national eID schemes, previous uptake of eIDs has been reluctant, and it's questionable whether an EU-wide rollout of eIDs will be successful.

But even if an EU-wide roll out was achievable, many will not be able to participate. Those who are not in possession of ID cards, passports, residence permits, or documents like birth certificates will not be able to attain an eID and will be at risk of losing access to knowledge, information, and services. This is especially relevant for already marginalized groups like refugees or unhoused people who may lose access to critical resources. But also many children and teenagers will not be able to participate in eID schemes. There are no EU-wide rules on when children need to have government-issued IDs, and while some countries, like Germany, mandate that every citizen above the age of 16 possess an ID, others, like Sweden, don’t require their citizens to have an ID or passport. In most EU Member States, the minimum age at which children can apply for an ID without parental consent is 18. So even in cases where children and teenagers may have a legal option to get an ID, their parents might withhold consent, thereby making it impossible for a child to verify their age in order to access information or services online.

The second option are so-called smartcards, or physical eID cards, such as national ID cards, e-passports or other trustworthy physical eID cards. The same limitations as for eIDs apply. Additionally, the Commission’s tender suggests the mini-ID wallet will rely on biometric recognition software to compare a user to the physical ID card they are using to verify their age. This leads to a host of questions regarding the processing and storing of sensitive biometric data. A recent study by the National Institute of Standards and Technology compared different age estimation algorithms based on biometric data and found that certain ethnicities are still underrepresented in training data sets, thus exacerbating the risk age estimation systems of discriminating against people of color. The study also reports higher error rates for female faces compared to male faces and that overall accuracy is strongly influenced by factors people have no control over, including “sex, image quality, region-of-birth, age itself, and interactions between those factors.” Other studies on the accuracy of biometric recognition software have reported higher error rates for people with disabilities as well as trans and non-binary people.

The third option foresees a procedure to allow for the verification of a user’s identity through institutions like a bank, a notary, or a citizen service center. It is encouraging that the Commission’s tender foresees an option for different, non-state institutions to verify a user’s age. But neither banks nor notary offices are especially accessible for people who are undocumented, unhoused, don’t speak a Member State’s official language, or are otherwise marginalized or discriminated against. Banks and notaries also often require a physical ID in order to verify a client’s identity, so the fundamental access issues outlined above persist.

Finally, the specification suggests that third party apps that already have verified a user's identity, like banking apps or mobile network operators, could provide age verification signals. In many European countries, however, showing an ID is a necessary prerequisite for opening a bank account, setting up a phone contract, or even buying a SIM card.

In summary, none of the options the Commission considers to allow for proving someone’s age accounts for the obstacles faced by different marginalized groups, leaving potentially millions of people across the EU unable to access crucial services and information, thereby undermining their fundamental rights.

The question of which institutions will be able to verify ages is only one dimension when considering the ramification of approaches like the mini-ID wallet for accessibility and participation. Although often forgotten in policy discussions, not everyone has access to a personal device. Age verification methods like the mini-ID wallet, which are device dependent, can be a real obstacle to people who share devices, or users who access the internet through libraries, schools, or internet cafés, which do not accommodate the use of personal age verification apps. The average number of devices per household has been found to correlate strongly with income and education levels, further underscoring the point that it is often those who are already on the margins of society who are at risk of being left behind by age verification mandates based on digital identities.

This is why we need to push back against age verification mandates. Not because child safety is not a concern – it is. But because age verification mandates risk undermining crucial access to digital services, eroding privacy and data protection, and limiting the freedom of expression. Instead, we must ensure that the internet remains a space where all voices can be heard, free from discrimination, and where we do not have to share sensitive personal data to access information and connect with each other.