This post is part of a series on Mastodon and the fediverse. We also have a post on what the fediverse is, why the fediverse will be great—if we don't screw it up, and how to make a Mastadon account. You can follow EFF on Mastodon here.

With so many users migrating to Mastodon as their micro-blogging service of choice, a lot of questions are being raised about the privacy and security of the platform. Though in no way comprehensive, we have a few thoughts we’d like to share on the topic.

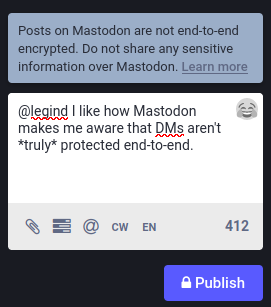

Essentially, Mastodon is about publishing your voice to your followers and allowing others to discover you and your posts. For basic security, instances will employ transport-layer encryption, keeping your connection to the server you’ve chosen private. This will keep your communications safe from local eavesdroppers using your same WiFi connection, but it does not protect your communications, including your direct messages, from the server or instance you’ve chosen—or, if you’re messaging someone from a different instance, the server they’ve chosen. This includes the moderators and administrators of those instances, as well. Just like Twitter or Instagram, your posts and direct messages are accessible by those running the services. But unlike Twitter or Instagram, you have the choice in what server or instance you trust with your communications. Also unlike the centralized social networks, the Mastodon software is relatively open about this fact.

Some have suggested that direct messages on Mastodon should be treated more like a courtesy to other users instead of a private message: a way to filter out content from their feeds that isn’t relevant to them, rather than a private conversation. But users of the feature may not understand that intent. We feel that the intended usage of the feature will not determine people’s expectation of privacy while using it. Many may expect those direct communications to have a greater degree of privacy.

Mastodon could implement direct message end-to-end encryption in the future for its clients. Engineering such a feature would not be trivial, but it would give users a good mechanism to protect their messages to one another. We hope to see this feature implemented for all users, but even a single forward-looking instance could choose to implement it for its users. In the meantime, if you need truly secure end-to-end direct messaging, we suggest using another service such as Signal or Keybase.

Despite its pitfalls, until recently Twitter had long had a strong security team. Mastodon is a largely volunteer-built platform undergoing growing pains, and some prominently used forks have had (and fixed) embarrassing vulnerabilities as of late. Though it’s been around since 2016, the new influx of users and new importance it has taken on will be a trial by force. We expect more bugs will be shaken from the tapestry before too long.

Two-factor authentication with an app or security key is available on Mastodon instances, giving users an extra security check to log on. The software also offers robust privacy controls: allowing users to set up automatic deletion of old posts, set personalized keyword filters, approve followers, and hide your social graph (the list of your followers and those you follow). Unfortunately, there is no analogue to making your account “private.” You can make a post viewable only by your followers at the time of posting, but you cannot change the visibility of your previous posts (either individually or in bulk).

Another aspect of “fediverse” (i.e., the whole infrastructure of federated servers that communicate with each other to provide a service) micro-blogging that differs from Twitter and affects the privacy of users is that there is no way to do a text search of all posts. This cuts down on harassment, because abusive accounts will have a harder time discovering posts and accounts using key words typically used by the population they’re targeting (a technique frequently used by trolls and harassers). In fact, the lack of text search is due to the federated nature of Mastodon: to implement this feature would mean every instance would have to be aware of every post made on every other instance. As it turns out, this is neither practical nor desirable. Instead, users can use hashtags to make their posts propagate to the rest of the fediverse and show up in searches.

Instances of Mastodon are also able to “defederate” from other instances if they find the content coming from the other instance to be abusive or distasteful, or in violation of their own policies on content. Say server A finds the users on server B to consistently be abusive, and chooses to defederate with it. “Defederating” will make all content from server B unavailable on server A, and users of server B cannot comment on posts of or direct message users of server A. Since users are encouraged to join Mastodon instances which align with their interests and attitudes on content and moderation, defederating gives instances and communities a powerful option to protect their users, with the goal of creating less adversarial and more convivial experience.

Centralized platforms are able to quickly determine the origin of fake or harassing accounts and block them across the entire platform. For Mastodon, it will take a lot more coordination to prevent abusive users that are suspended on one instance from just creating a new account on another federated instance. This level of coordination is not impossible, but it takes effort to establish.

Individuals also have powerful tools to control their own user experience. Just like on the centralized platforms, Mastodon users can mute, block, or report other users. Muting and blocking works just as you’d expect: it’s a list associated with your account that just stops the content of that user from appearing in your feed and prevents them from reaching out to you, respectively. Reporting is a bit different: since there is no centralized authority removing user accounts, this option allows you to report an account to your own instance’s moderators. If the user being reported is on the same instance as you, the instance can choose to suspend or freeze that user account. If the user is on another instance, your instance may block that user for all its users, or (if there is a pattern of abuse coming from that instance), it may also choose to defederate as described above. You can additionally choose to report the content to the moderators of that user's instance, if desired.

Federation gives Mastodon users a fuzzy “small town” feeling because your neighbors are those on the same instance as you. There’s even a feed just for your neighbors: “Local.” And since you’re likely to choose an instance with others of similar interests and moderators who want to protect their community of users, they are likely to tweak their moderation practices in a way that keeps their users’ accounts private from groups and individuals who may be predatory or adversarial.

There is a concern that Mastodon may promote insular communities and echo chambers. In some ways this is a genuine risk: encouraging users to join communities of their own interests may make them more likely to encounter other users who are just like them. However, for some people this will be a benefit. The universal and instantaneous ubiquity of posts made on Twitter puts everyone within swinging distance of everyone else, and the mechanisms to filter out hateful content have in the past been widely criticized as ineffective, arbitrary, and without recourse. More recently, even those limited and ineffective mechanisms have been met by Twitters’ new leader with open hostility. Is it any wonder why users are flocking to the small town with greener pastures, one that allows you to easily move your house to the next town over if you don’t like it there, rather than bulldozing the joint?

In 2022, user experience is a function of the privacy and content policies offered by services. Federation makes it possible to have a diverse landscape of different policies, attentive to their own users' attitudes and community customs, while still allowing communication outside those communities to a broader audience. It will be exciting to see how this landscape evolves.