It's become easier over the years for websites to improve their security, thanks to tools that allow more people to automate and easily set-up secure measures for web applications and the services they provide. A proposed amendment to Article 45 in the EU’s Digital Identity Framework (eIDAS) would roll back these gains by requiring outdated ideas for security and authentication of websites. The amendment states that “web-browsers shall ensure that the identity data provided using any of the methods is displayed in a user-friendly manner.” The amendment proposal emphasizes a specific type of documentation, Qualified Web Authentication Certificates, or QWACs, to accomplish this goal. The problem is that, simply put, the approach the amendment suggests has already been debunked as an effective way to convey security to users.

The Quacks in QWACs

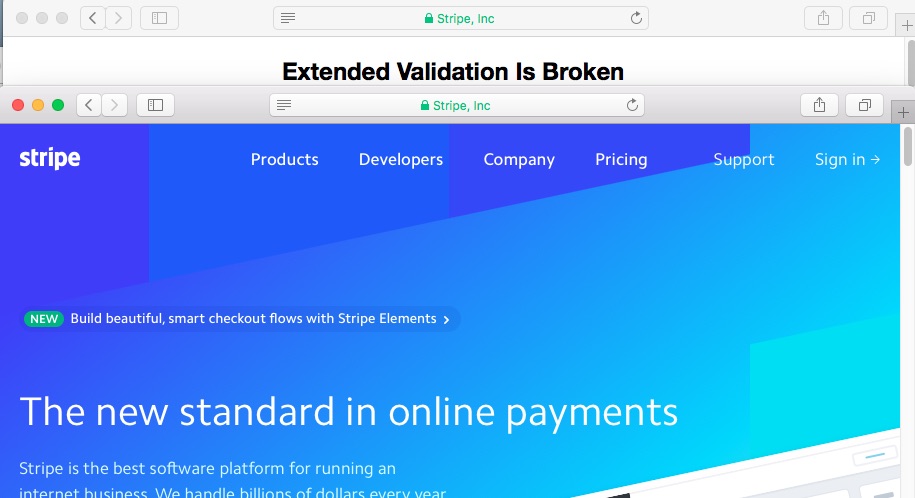

QWACs use guidelines similar to Extended Validation (EV) certificates. Both are digital certificates issued to domain owners with an added process that establishes an identity check on the domain owner. This approach has been proven ineffective over the years.

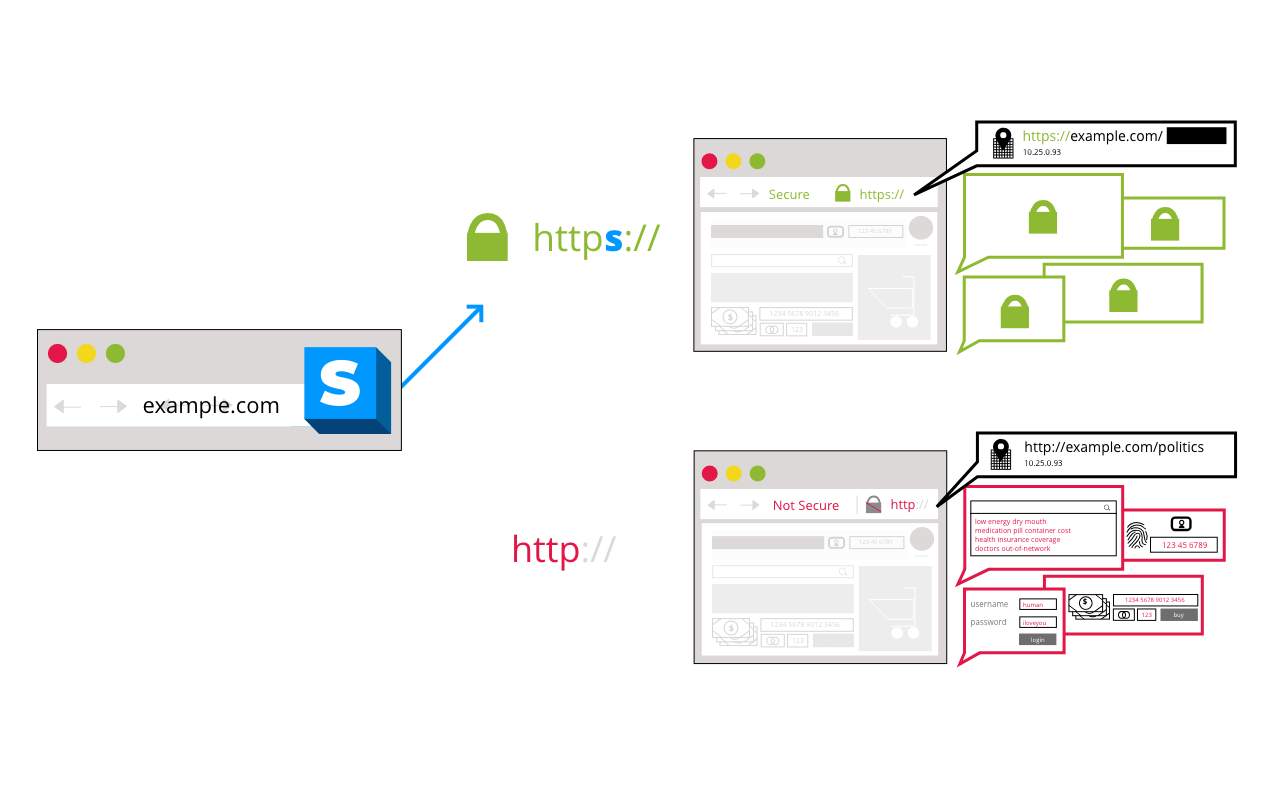

For a short while, browsers made a point of showing EV certificates to the user, displaying the certificate details in green. They assumed that this clear marker would indicate more security for users. However, nefarious parties ended up obtaining EV Certificates and hosting phishing sites. This highlights that HTTPS—supported by certificates—establishes a secure connection between you and that website, but does not guarantee the website itself is storing or using the information you may submit to it ethically. Nor is it an assurance that a company's business practices are sound. That is what consumer protection laws are for.

Because emphasizing these certificates proved ineffective in helping user security, Chrome and Firefox in 2019 decided to no longer emphasize EV Certified websites in the URL bar. Safari stopped in late 2018. However, EV certificates are significantly more expensive and some Certificate Authorities (CAs) that sell them still inaccurately suggest that browsers emphasize EV certificates in their sales pitch for these products. Requiring that QWACs be displayed in the same fashion is just further pursuing the illusion that displaying identity information to the user will be worth the effort.

Potential Fowl Play with User Experience

Requiring browsers to trust these certificates by EU government-mandated CAs, could impact users outside the EU as well. Rather than improve security as intended, this would likely force the adoption of a security-hindering feature into the internet experiences of users within and outside the EU. People could be susceptible to poor response of security incidents with EU-mandated CAs, breach of privacy, or malware targeting.

It’s even been ludicrously suggested by Entrust (a CA) that any website that doesn’t use QWACs or EV certificates be flagged by the browser with a warning to the user when they submit data. Such a warning would make no sense, because standard Domain Validation (DV) certificates provide the same security for data in transit as EV does.

Trust Services Forum - CA Day 2021

Transport Layer Security (TLS) is the backbone to secure your connection to a website. When this occurs, it is called HTTPS. Think of it as HTTP(S)ecure.

Browsers have worked for years to show people that their connection is secure without confusing them. This proposal would undo much of that user education by potentially unleashing a flood of warnings for sites that were actually adequately secured with DV certificates.

If It Walks Like an EV Cert and Flies Like an EV Cert—Maybe It Is an EV cert

This amendment also makes problematic assumptions about how much consumers know about the identity of companies. Large corporations like Unilever own many products and brands, for example, and consumers may not realize that. Some well known brands, like Volvo automobiles, are owned by companies with seemingly unrelated names. It’s also not impossible for two companies that offer completely different products to share a name; the marketing term “brand twins” describes this. Examples include Delta Airlines and Delta Faucet, or Apple Records and tech giant Apple, Inc.

Researcher Ian Carroll filed the necessary paperwork to incorporate a business called Stripe Inc

For these reasons, it is nearly impossible for a QWAC to achieve its stated goal of making the entity that owns a domain easily apparent to the people visiting a website—especially across the globe. QWACs also put up a weak defense against the simplest and most effective forms of hacking: social engineering. The very people—scammers, phishers, etc.—who are allegedly hindered with an EV or QWAC certificate, have and will find a way around them, because the validation process is still led by humans. Also, we shouldn’t endorse the dangerous premise that only the “right people” — in other words, those who can afford it—should have encrypted services.

This proposal to bind TLS to a legal identity across all domains that qualify is not achievable or scalable. QWACs will not readily solve this issue on the modern web or with mobile applications either; even with their slight technical differences from EV. Mozilla and other vendors (Apple, Google, Microsoft, Opera, and Vivaldi) have made sufficient suggestions for eIDAS to validate identity without binding identity to the TLS deployment process itself or using TLS Certificates at all. The push to use QWACs to achieve this goal is a detrimental framework that would discourage affordable and more efficient TLS.

Ducking Up TLS Deployment

Interoperability across borders is a great ideal to have, but the mandate to emphasize QWACs in the browser ironically hinders interoperability. The eIDAS Article 45 proposal attempts to guarantee the legal and safe identity of the website owner—but that is not the problem TLS was built to solve.

Standard Domain Validated certificates by CAs have achieved the level of security that website visitors need globally. Tools like Certbot and the free CA Let’s Encrypt have contributed to making TLS deployment and automation more widespread and accessible. Today, domain owners can utilize automated hosting services for services between businesses and with their own customers that alleviate traffic-handling and optimizing costs. Mandating QWAC emphasis threatens to set us back. Domain owners will likely have to use self-managed certificate options to maintain their web security. That would increase inequality across the internet. A large company can acquire the infrastructure to do this; They may even achieve partial automation, as has happened with EV certificates. However, smaller companies and individuals may not be able to acquire these tools as easily. Requiring all domain owners to have the technical expertise and the monetary resources to self-manage their certificates sets TLS deployment back 6 years, by raising the difficulty and barriers to complying with the eIDAS regulation.

This is all very reminiscent of a time when TLS deployment was more difficult, costly, and time consuming. This amendment to emphasize QWACs in the browser frames free security as bad security. In this case, that is neither truthful nor useful to internet users everywhere.

This post was updated on 2/9/22 to correct the involvement of the joint position paper linked in this post: https://blog.mozilla.org/netpolicy/files/2020/10/2020-10-01-eIDAS-Open-Public-Consultation-EU-Commission-.pdf