On the biggest internet platforms, content moderation is bad and getting worse. It’s difficult to get it right, and at the scale of millions or billions of users, it may be impossible. It’s hard enough for humans to sift between spam, illegal content, and offensive but legal speech. Bots and AI have also failed to rise to the job.

So, it’s inevitable that services make mistakes—removing users’ speech that does not violate their policies, or terminating users’ accounts with no explanation or opportunity to appeal. And inconsistent moderation often falls hardest on oppressed groups.

The dominance of a handful of online platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter increases the impact of their content moderation decisions and mistakes on internet users’ ability to speak, organize, and participate online. Bad content moderation is a real problem that harms internet users.

There’s no perfect solution to this issue. But U.S. lawmakers seem enamored with trying to force platforms to follow a government-mandated editorial line: host this type of speech, take down this other type of speech. In Congressional hearing after hearing, lawmakers have hammered executives of the largest companies over what content stayed up, and what went down. The hearings ignored smaller platforms and services that could be harmed or destroyed by many of the new proposed internet regulations.

Lawmakers also largely ignored worthwhile efforts to address the outsized influence of the largest online services—like legislation supporting privacy, competition, and interoperability. Instead, in 2021, many lawmakers decided that they themselves would be the best content moderators. So EFF fought off, and is continuing to fight off, repeated government attempts to undermine free expression online.

The Best Content Moderators Don’t Come From Congress

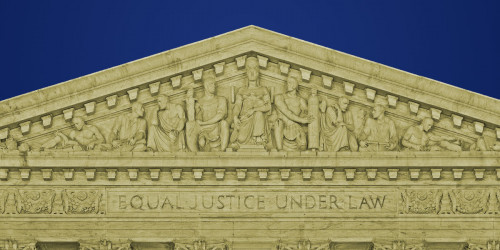

It’s a well-established part of internet law that individual users are responsible for their own speech online. Users and the platforms distributing users’ speech are generally not responsible for the speech of others. These principles are embodied in a key internet law, 47 U.S.C. § 230 (“Section 230”), which prevents online platforms from being held liable for most lawsuits relating to their users’ speech. The law applies to small blogs and websites, users who republish others’ speech, as well as the biggest platforms.

In Congress, lawmakers have introduced a series of bills that suggest online content moderation will be improved by removing these legal protections. Of course, it’s not clear how a barrage of expensive lawsuits targeting platforms will improve online discourse. In fact, having to potentially litigate every content moderation decision will actually make hosting online speech prohibitively expensive, meaning that there will be strong incentives to censor user speech whenever anyone complains. Anyone who’s not a Google or a Facebook will have a very hard time affording to run a website that hosts user content, that is also legally compliant.

Nevertheless, we saw bill after bill that actively sought to increase the number of lawsuits over online speech. In February, a group of Democratic senators took a shotgun-like approach to undermining internet law, the SAFE Tech Act. This bill would have knocked out Section 230 from applying to speech in which “the provider or user has accepted payment” to create the speech. If it had passed, SAFE Tech would have both increased censorship and hurt data privacy (as more online providers switched to invasive advertising, and away from “accepting payment,” which would cause them to lose protections.)

The following month, we saw the introduction of a revised PACT Act. Like the SAFE Tech Act, PACT would reward platforms for over-censoring user speech. The bill would require a “notice and takedown” system in which platforms remove user speech when a requestor provides a judicial order finding that the content is illegal. That sounds reasonable on its face, but the PACT Act failed to provide safeguards, and would have allowed for would-be censors to delete speech they don’t like by getting preliminary or default judgments.

The PACT Act would also mandate certain types of transparency reporting, an idea that we expect to see come back next year. While we support voluntary transparency reporting (in fact, it’s a key plank of the Santa Clara Principles), we don’t support mandated reporting that’s backed by federal law enforcement, or the threat of losing Section 230’s protections. Besides being bad policy, these regulations would intrude on services’ First Amendment rights.

Last but not least, later in the year we grappled with the Justice Against Malicious Algorithms, or JAMA Act. This bill’s authors blamed problematic online content on a new mathematical boogeyman: “personalized recommendations.” JAMA Act removes Section 230 protections for platforms that use a vaguely-defined “personal algorithm” to suggest third-party content. JAMA would make it almost impossible for a service to know what kind of curation of content might render it susceptible to lawsuits.

None of these bills have been passed into law—yet. Still, it was dismaying to see Congress continue down repeated dead-end pathways this year, trying to create some kind of internet speech-control regime that wouldn’t violate the Constitution and produce widespread public dismay. Even worse, lawmakers seem completely uninterested in exploring real solutions, such as consumer privacy legislation, antitrust reform, and interoperability requirements, that would address the dominance of online platforms without having to violate users’ First Amendment rights.

State Legislatures Attack Free Speech Online

While Democrats in Congress expressed outrage at social media platforms for not removing user speech quickly enough, Republicans in two state legislatures passed laws to address the platforms’ purported censorship of conservative users’ speech.

First up was Florida, where Gov. Ron DeSantis decried Twitter’s ban of President Donald Trump and other “tyrannical behavior” by “Big Tech.” The state’s legislature passed a bill this year that prohibits social media platforms from banning political candidates, or deprioritizing any posts by or about them. The bill also prohibits platforms from banning large news sources or posting an “addendum” (i.e., a fact check) to the news sources’ posts. Noncompliant platforms can be fined up to $250,000 per day, unless the platform also happens to own a large theme park in the state. A Florida state representative who sponsored the bill explained that this exemption was designed to allow the Disney+ streaming service to avoid regulation.

This law is plainly unconstitutional. The First Amendment prohibits the government from requiring a service to let a political candidate speak on their website, any more than it can require traditional radio, TV, or newspapers to host the speech of particular candidates. EFF, together with Protect Democracy, filed a friend-of-the-court brief in a lawsuit challenging the law, Netchoice v. Moody. We won a victory in July, when a federal court blocked the law from going into effect. Florida has appealed the decision, and EFF has filed another brief in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit.

Next came Texas, where Governor Greg Abbott signed a bill to stop social media companies that he said “silence conservative viewpoints and ideas.” The bill prohibits large online services from moderating content based on users’ viewpoints. The bill also required platforms to follow transparency and complaint procedures. These requirements, if carefully crafted to accommodate constitutional and practical concerns, could be appropriate as an alternative to editorial restrictions. But in this bill, they are part and parcel of a retaliatory, unconstitutional law.

This bill, too, was challenged in court, and EFF again weighed in, telling a Texas federal court that the measure is unconstitutional. The court recently blocked the law from going into effect, including its transparency requirements. Texas is appealing the decision.

A Path Forward: Questions Lawmakers Should Ask

Proposals to rewrite the legal underpinnings of the internet came up so frequently this year that at EFF, we’ve drawn up a more detailed process of analysis. Having advocated for users’ speech for more than 30 years, we’ve developed a series of questions lawmakers should ask as they put together any proposal to modify the laws governing speech online.

First we ask, what is the proposal trying to accomplish? If the answer is something like “rein in Big Tech,” the proposal shouldn’t impede competition from smaller companies, or actually cement the largest services’ existing dominance. We also look at whether the legislative proposal is properly aimed at internet intermediaries. If the goal is something like stopping harassment, or abuse, or stalking—those activities are often already illegal, and the problem may be better solved with more effective law enforcement, or civil actions targeting the individuals perpetuating the harm.

We’ve also heard an increasing number of calls to impose content moderation through the infrastructure level. In other words, shutting down content by getting an ISP or a content delivery network (CDN) to take certain action, or a payment processor. These intermediaries are potential speech “chokepoints” and there are serious questions that policymakers should think through before attempting infrastructure-level moderation.

We hope 2022 will bring a more constructive approach to internet legislation. Whether it does or not, we’ll be there to fight for users’ right to free expression.

This article is part of our Year in Review series. Read other articles about the fight for digital rights in 2021.