The tech companies behind the so-called “sharing economy” have drawn the ire of brick-and-mortar businesses and local governments across the country.

For example, take-out apps such as GrubHub and UberEats have grown into a hundred-billion-dollar industry over the past decade, and received a further boost as many sit-down restaurants converted to only take-out during the pandemic. Small businesses are upset, in part, that these companies are collecting and monetizing data about their customers.

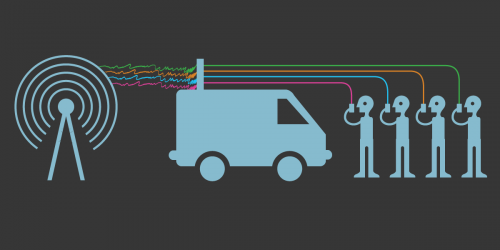

Likewise, ride-sharing services have decimated the highly-regulated taxi industry, replacing it with a larger, more nebulous fleet of personal vehicles carrying passengers around major cities. This makes them harder to regulate and plan around than traditional taxis. Alarmed municipal transportation agencies feel that they do not have the tools they need to monitor and manage ride-sharing.

A common thread runs through these emerging industries: massive volumes of sensitive personal data. Yelp, Grubhub, Uber, Lyft, and many more new companies have inserted themselves in between customers and older, smaller businesses, or have replaced those businesses entirely. The new generation of tech companies collect more data about their users than traditional businesses ever did. A restaurant might know its regular customers, or keep track of its best-selling dishes, but Grubhub can track each user’s searches, devices, and meals at restaurants across the city. Likewise, while traditional taxi services may have logged trip times, origins, and destinations, Uber and Lyft can link each trip to a user’s real-world identity and track supply and demand in real time.

This data is attractive for several reasons. It can be monetized through targeted ads or sold directly to data brokers, and it gives larger companies a competitive advantage over their smaller, less information-hungry peers. It allows tech companies to observe market trends, informing decisions about pricing, worker pay, and whom to buy out next. Sharing-economy corporations have every incentive to collect as much data as possible, and few legal restrictions on doing so. As a result, our interactions with everyday services like restaurants are tracked more closely than ever before.

Legislators want to force tech companies to share data

Several bills in states around the country, including in California and New York City, propose a “solution”: force the tech companies to share some of the data they collect. But these bills are misguided. While they might give small businesses short-term boons, they won’t address the larger systems that have led to corporate concentration in the tech sector. They will further encourage the commoditization of our data as a tool for businesses to battle each other, with user privacy caught in the crossfire.

Normalizing new, indiscriminate data sharing is a problem. Instead, regulators should be thinking of ways to protect consumers by limiting data collection, retention, use, and sharing. Creating new mandates to share data simply puts it in the hands of more businesses. This opens up more ways for government seizure of that data and more targets for hackers.

We’ve sung the praises of interoperability policy in the past, so how is this different? After all, if Facebook should have to share data with its competitors under something like the ACCESS Act, why shouldn’t UberEats have to share data with restaurants? The difference is who’s in control. Good interoperability policy should put the user front and center: data sharing must only happen with a user’s opt-in consent, and only for purposes that directly benefit the user.

Forcing DoorDash to share information with restaurants, or Uber to share data with cities, doesn’t serve users in any way. And these bills don’t require a user’s opt-in consent for the processing of their data. Instead, these policies would make it so that sharing data with one company means that data will automatically end up in the hands of several downstream parties. Since the United States lacks basic consumer privacy laws, recipients of this data will be free to sell it, otherwise monetize it, or share it with law enforcement or immigration officials. This further erodes what little agency users currently have.

Regulation should aim to protect user rights

The collection and use of personal data by tech companies is a real problem. And big companies wield their data troves as weapons to beat back competitors. But we should address those problems directly: first, with strong privacy laws governing how businesses process our data; and second, with better antitrust enforcement that puts a stop to harmful conglomeration and anticompetitive behavior.

It’s also okay for regulators to monitor and manage ride-sharing and other services that impact the public by requiring reasonable amounts of aggregated and deidentified data. Uber and Lyft have a well-documented history of deliberately misleading local authorities in order to skirt laws. However, any data-sharing requirements must be limited in scope, and minimize the risks to individual users and their data. For example, rules should carefully consider how much information is actually necessary to achieve specific governmental goals. Often, such information need not be highly granular. Whether the government or a private company is holding information, reidentification is always a real concern—by city transportation agencies, law enforcement, ICE, or any other third parties that purchase or steal data.

Despite what aspiring government contractors may say, agencies should not collect huge amounts of individualized data up front, then figure out what to do with it later. The way to fix bad actors in tech is not to increase non-consensual data sharing—nor to have governments mimic bad actors in tech.