In 2005, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) made a foundational decision on how broadband competition policy would work with the entry of fiber to the home. In short, the FCC concluded that competition was growing, government policy was unnecessary in deference to market forces, and that the era of communications monopoly was rapidly ending. The very next year at the request of companies like Verizon and AT&T, some states, including California, passed laws that consolidated local “franchises” into single statewide franchises, making the same assumption that the FCC did.

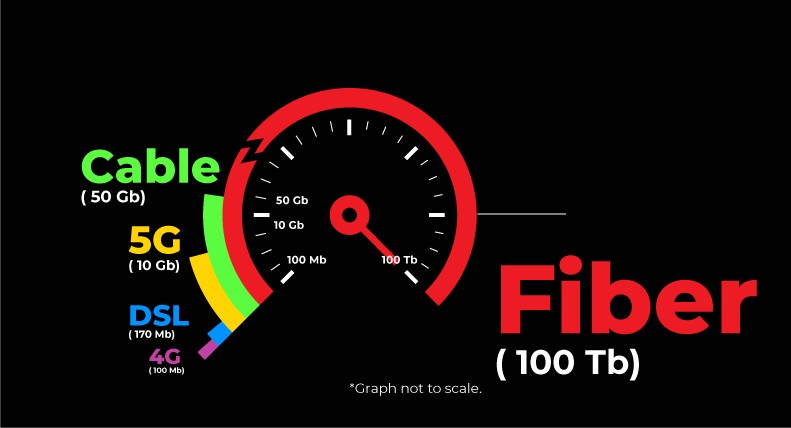

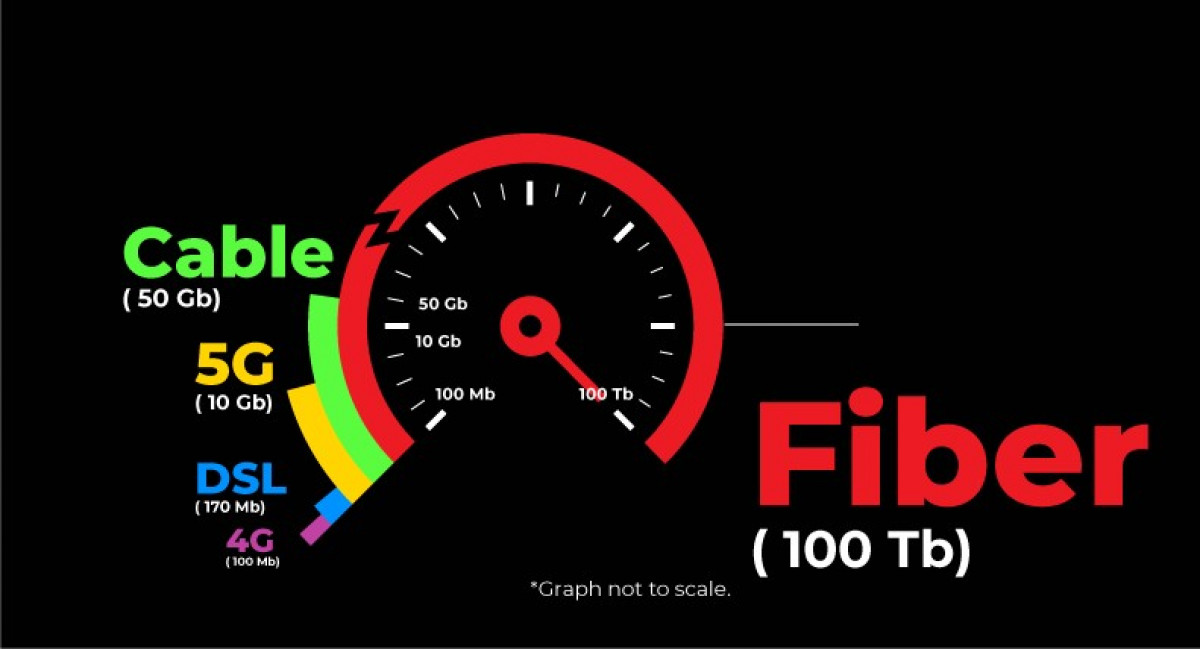

When you look at communities in the aggregate, you would be hard-pressed to find a single large American city where you couldn’t turn a profit with fiber.

They were wrong. To explore just how wrong, EFF and the Technology Law and Policy Center have published our newest white paper on the effects of these decisions. The research digs into New York, which decided to retain power at the local level and see what we can learn from the state as we look to the future. The big takeaway is that large cities that do not have local franchise authority are losing out because they lack the negotiating leverage needed to push private fiber to all city residents, particularly low-income residents.

What are Franchises and Why Did They Change in 2006?

Franchises are basically the negotiated agreement between broadband carriers and local communities on how access will be provisioned—essentially, a license to do business in the area. These franchises exist because Internet service providers (ISPs) need access to the taxpayer-funded rights of way infrastructure such as roads, sewers, and other means of traveling throughout a community (and notably it would be impossible for ISPs to try to bypass the existing public infrastructure). ISPs also benefit because these agreements conveniently lay out a roadmap for deploying broadband access. The public interest goal of a franchise is to come to an agreement that is fair to the taxpayer for creating the infrastructure.

Earlier franchises were used by the cable television industry to secure a monopoly in a city in exchange for widespread deployment. The city would agree to the monopoly as long as the cable company built out to everyone. This is very similar to the original agreement AT&T secured from the federal government back in the telephone monopoly era. The cable TV monopoly status was, in turn, used to secure preferential financing to fund the construction of the coaxial cable infrastructure that we still mostly use today (although much of that infrastructure has been converted to hybrid fiber/cable, with the cable part still connected to residential dwellings). The cable industry made the argument to the banks when securing funding that because it had no competitors in a community, it would be able to pay back corporate debt quite easily. That part, at least, worked very well; cable is widespread today in cities. Congress later abolished monopolies in franchising in 1992 with the passage of the Cable Television Consumer Protection and Competition Act, which also forced negotiation between cable and television broadcasters.

In 2005, Verizon, which was set to launch their FiOS fiber network, led a lobbying effort in DC to rethink local franchising power. The broadband industry as a whole was hoping for a simpler process than having to negotiate city by city (like cable). After securing a massive deregulatory gift from the FCC’s decision to classify broadband as an information service not subject to federal competition policy of the 90s—or, as we found out years later in the courts, to net neutrality—the broadband industry wanted new rules for fiber to the home.

Local governments without full local franchise power are extraordinarily constrained when it comes to pushing private service providers.

The industry argument was that we were no longer in the monopoly era of communications (spoiler alert: we are very much in a monopoly era for broadband access), and that competition would do the work to meet the policy goals of universal, affordable, and open Internet services. Congress came very close to agreeing to eliminate franchise authority and take it away from local communities in 2006, but the bill was stalled in the Senate by a bipartisan pair of Senators who wanted net neutrality protections. In response to their loss in Congress, Verizon and others took their argument to the states. Just months later they secured statewide franchising in California. They failed to secure the same change in New York. The industry’s failure there gives us the opportunity to compare two very large states and big cities to see how both approaches have played out for communities.

New York Shows That Local Franchising Works for Big Cities

Local governments without full local franchise power are extraordinarily constrained when it comes to pushing private service providers. With franchise power, local problems are hashed out during negotiations, when communities and companies are considering the mutual benefit of expanded private broadband services in exchange for access to the taxpayer-funded public rights of way. Without it, those negotiations never take place.

As Verizon lobbied to eliminate local franchising, New York’s state legislature studied the issue thoroughly through their state public utilities commission (PUC). The PUC’s research noted that local power promotes local competition and addresses antitrust concerns with communications infrastructure and that competition requires special attention to promote new, smaller entrants. Public interest regulation tailored for large incumbents to prevent discrimination was concluded to be best done at the local level. After their research, New York decided not to eliminate local franchising, and has stayed the course despite 16 years of lobbying by the big ISPs.

The benefits of this decision are clearly illustrated in New York City, which understood that its massive population, wealthy communities, business sector, and density would allow Verizon to deliver fiber to every single home for a profit. This was signed into a franchise in 2008. When Verizon discontinued its fiber service expansion in 2010, the city reminded the company that they had an agreement. Verizon tried to argue that the law's requirement that service “pass” a home—commonly understood as meaning connecting the home—just meant that fiber was somewhere near the house, and argued that wireless broadband was the same. The city decided to take Verizon to court to enforce their franchise in 2014. While the litigation was lengthy, in November 2020 the city secured a settlement from Verizon to build another 500,000 fiber to the home connections to low income communities. Compare that to California big cities like Oakland and Los Angeles, where studies are showing rampant digital redlining of fiber against low-income people, particularly for black neighborhoods.

Big Cities Should Be 100 Percent Fibered, But They Need Their Power Back

Carriers often want policymakers to think about broadband deployment as an isolated house-by-house effort, rather than community-wide or regional efforts. They do this to justify the digital redlining of fiber that happens across the country in cities that lack power to stop it.

Our research shows that when you narrow in on a per household basis, you find that some homes aren’t profitable to connect in isolation. But when you look at communities in the aggregate, you would be hard-pressed to find a single large American city where you couldn’t turn a profit with fiber. That only comes from averaging out your costs and averaging out your profits—and laws that prohibit socioeconomic discrimination in broadband deployment force averaging rather than isolating. If states want more private fiber to be expanded in their big cities, it appears clear that allowing cities to negotiate on their own behalf is one powerful option that needs to be restored, particularly in California. It won’t solve the entire problem, but it can be a piece of how we get fiber to every home and business.

For a more in-depth look at the issue, read more in the whitepaper.