This blog post was co-written by EFF intern Haley Amster.

EFF filed an amicus brief in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the First Circuit urging the court to hold that under the First Amendment public schools may not punish students for their off-campus speech, including posting to social media while off campus.

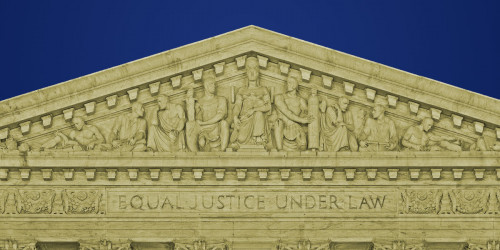

The Supreme Court has long held that students have the same constitutional rights to speak in their communities as do adults, and this principle should not change in the social media age. In its landmark 1969 student speech decision, Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, the Supreme Court held that a school could not punish students for wearing black armbands at school to protest the Vietnam War. In a resounding victory for the free speech rights of students, the Court made clear that school administrators are generally forbidden from policing student speech except in a narrow set of exceptional circumstances: when (1) a student’s expression actually causes a substantial disruption on school premises; (2) school officials reasonably forecast a substantial disruption; or (3) the speech invades the rights of other students.

However, because Tinker dealt with students’ antiwar speech at school, the Court did not explicitly address the question of whether schools have any authority to regulate student speech that occurs outside of school. At the time, it may have seemed obvious that students can publish op-eds or attend protests outside of school, and that the school has no authority to punish students for that speech even if it’s highly controversial and even if other students talk about it in school the next day. As we argued in our amicus brief, the Supreme Court’s three student speech cases following Tinker all involved discipline related to speech that may reasonably be characterized as on-campus.

In the social media age, the line between off- and on-campus has been blurred. Students frequently engage in speech on the Internet outside of school, and that speech is then brought into school by students on their smartphones and other mobile devices. Schools are increasingly punishing students for off-campus Internet speech brought onto campus.

In our amicus brief, EFF urged the First Circuit to make clear that schools have no authority under Tinker to police students’ off-campus speech, including when that speech occurs on social media. The case, Doe v. Hopkinton, involves two public high school students, “John Doe” and “Ben Bloggs,” who were suspended for making comments in a private Snapchat group that their school considered to be bullying. Doe and Bloggs filed suit asserting that the school suspension violated their First Amendment rights.

The school made no attempt to show in the lower court that Doe and Bloggs sent the messages at issue while on campus, and the federal judge erroneously concluded that “it does not matter whether any particular message was sent from an on- or off-campus location.”

As we explained in our amicus brief, that conclusion was wrong. Tinker made clear that students’ speech is entitled to First Amendment protection, and authorized schools to punish student speech only in narrow circumstances to ensure the safety and functioning of the school. The Supreme Court has never authorized or suggested that public schools have any authority to reach into students’ private lives and punish them for their speech while off school grounds or after school hours.

This is exactly what another federal appeals court considering this question concluded last summer. In B.L. v. Mahanoy Area School District, a high school student who had failed to advance from junior varsity to the varsity cheerleading squad posted a Snapchat selfie over the weekend with text that said, among other things, “fuck cheer.” One of her Snapchat connections took a screen shot of the post and shared it with the cheerleading coaches, who suspended the student from participation in the junior varsity cheer squad.

The Third Circuit in Mahanoy made clear that the narrow set of circumstances established in Tinker where a school may regulate disruptive student speech applies only to speech uttered at school. As such, it held that schools have no authority to punish students for their off-campus speech—even when that speech “involves the school, mentions teachers or administrators, is shared with or accessible to students, or reaches the school environment.”

This conclusion is especially critical given that students use social media to engage in a wide variety of self-expression, political speech, and activism. As we highlighted in our amicus brief, this includes expressing dissatisfaction with their schools’ COVID-19 safety protocols, calling out instances of racism at schools, and organizing protests against school gun violence. It is essential that courts draw a bright line prohibiting schools from policing off-campus speech so that students can exercise their constitutional rights outside of school without fear that they might be punished for it come Monday morning.

Mahanoy is currently on appeal to the Supreme Court, which will consider the case this spring. We hope that the First Circuit and the Supreme Court will take this opportunity to reaffirm the free speech rights of public-school students and draw clear limits on schools’ ability to police students’ private lives.