The U.S. House Judiciary Committee held a hearing this week to discuss the spread of white nationalism, online and offline. The hearing tackled hard questions about how online platforms respond to extremism online and what role, if any, lawmakers should play. The desire for more aggressive moderation policies in the face of horrifying crimes is understandable, particularly in the wake of the recent massacre in New Zealand. But unfortunately, looking to Silicon Valley to be the speech police may do more harm than good.

When considering measures to discourage or filter out unwanted activity, platforms must consider how those mechanisms might be abused by bad actors. Similarly, when Congress considers regulating speech on online platforms, it must consider both the First Amendment implications and how its regulations might unintentionally encourage platforms to silence innocent people.

When considering measures to discourage or filter out unwanted activity, platforms must consider how those mechanisms might be abused by bad actors.

Again and again, we’ve seen attempts to more aggressively stamp out hate and extremism online backfire in colossal ways. We’ve seen state actors abuse flagging systems in order to silence their political enemies. We’ve seen platforms inadvertently censor the work of journalists and activists attempting to document human rights atrocities.

But there’s a lot platforms can do right now, starting with more transparency and visibility into platforms’ moderation policies. Platforms ought to tell the public what types of unwanted content they are attempting to screen, how they do that screening, and what safeguards are in place to make sure that innocent people—especially those trying to document or respond to violence—aren’t also censored. Rep. Pramila Jayapal urged the witnesses from Google and Facebook to share not just better reports of content removals, but also internal policies and training materials for moderators.

Better transparency is not only crucial for helping to minimize the number of people silenced unintentionally; it’s also essential for those working to study and fight hate groups. As the Anti-Defamation League’s Eileen Hershenov noted:

To the tech companies, I would say that there is no definition of methodologies and measures and the impact. […] We don’t have enough information and they don’t share the data [we need] to go against this radicalization and to counter it.

Along with the American Civil Liberties Union, the Center for Democracy and Technology, and several other organizations and experts, EFF endorses the Santa Clara Principles, a simple set of guidelines to help align platform moderation practices to human rights and civil liberties principles. The Principles ask platforms

- to be honest with the public about how many posts and accounts they remove,

- to give notice to users who’ve had something removed about what was removed, and under what rule, and

- to give those users a meaningful opportunity to appeal the decision.

Hershenov also cautioned lawmakers about the dangers of heavy-handed platform moderation, pointing out that social media offers a useful view for civil society and the public into how and where hate groups organize: “We do have to be careful about whether in taking stuff off of the web where we can find it, we push things underground where neither law enforcement nor civil society can prevent and deradicalize.”

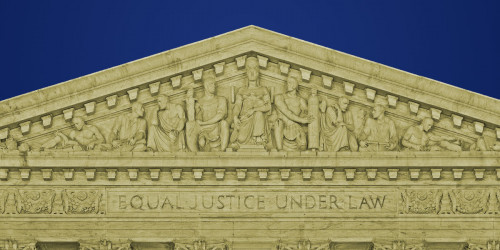

Before they try to pass laws to remove hate speech from the Internet, members of Congress should tread carefully. Such laws risk pushing platforms toward a more highly filtered Internet, silencing far more people than was intended. As Supreme Court Justice Anthony Kennedy wrote in Matel v. Tam (PDF) in 2017, “A law that can be directed against speech found offensive to some portion of the public can be turned against minority and dissenting views to the detriment of all.”