EFF had high hopes that the Domain Name Association's Healthy Domains Initiative (HDI) wouldn't be just another secretive industry deal between rightsholders and domain name intermediaries. Toward that end, we and other civil society organizations worked in good faith on many fronts to make sure HDI protected Internet users as well.

Those efforts seem to have failed. Yesterday, the Domain Name Association (DNA), a relatively new association of domain registries and registrars, suddenly launched a proposal for "Registry/Registrar Healthy Practices" on a surprised world, calling on domain name companies to dive headlong into a new role as private arbiters of online speech. This ill-conceived proposal is the very epitome of Shadow Regulation. There was no forewarning about the release of this proposal on the HDI mailing list; indeed, the last update posted there was on June 9, 2016, reporting "some good progress," and promising that any HDI best practice document "will be shared broadly to this group for additional feedback." That never happened, and neither were any updates posted to HDI's blog.

While yesterday's announcement claims that "civil society" was part of a "year-long process of consultation" leading to this document, it doesn't say which groups participated, or how they were selected. In any purported effort to develop a set of community-based principles, a failure to proactively reach out to affected stakeholders, especially if they have already expressed interest, exposes the effort as a sham. "Inclusion" is one of the three key criteria that EFF developed in explaining how fair processes can lead to better outcomes, and this means making sure that all stakeholders who are affected by Internet policies have the opportunity to be heard. The onus here lies on the organization that aims to develop those policies, and in this the DNA has clearly failed.

Copyright Censorship Through Compulsory Private Arbitration

So, what did HDI propose in its Registry/Registrar Healthy Practices [PDF]? The Practices divide into four categories, quite different from one another: Addressing Online Security Abuse, Complaint Handling for “Rogue” Pharmacies, Enhancing Child Abuse Mitigation Systems, and Voluntary Third Party Handling of Copyright Infringement Cases. We will focus for now on the last of these, because it is the newest and most overreaching voluntary enforcement mechanism described in the Practices.

The HDI recommends the construction of "a voluntary framework for copyright infringement disputes, so copyright holders could use a more efficient and cost-effective system for clear cases of copyright abuse other than going to court." This would involve forcing everyone who registers a domain name to consent to an alternative dispute resolution (ADR) process for any copyright claim that is made against their website. This process, labelled ADRP, would be modeled after the Uniform Dispute Resolution Policy (UDRP), an ADR process for disputes between domain name owners and trademark holders, in which the latter can claim that a domain name infringes its trademark rights and have the domain transferred to their control.

This is a terrible proposal, for a number of reasons. First and foremost, a domain name owner who contracts with a registrar is doing so only for the domain name of their website or Internet service. The content that happens to be posted within that website or service has nothing to do with the domain name registrar, and frankly, is none of its business. If a website is hosting unlawful content, then it is the website host, not the domain registrar, who needs to take responsibility for that, and only to the extent of fulfilling its obligations under the DMCA or its foreign equivalents.

Second, it seems too likely that any voluntary, private dispute resolution system paid for by the complaining parties will be captured by copyright holders and become a privatized version of the failed Internet censorship bills SOPA and PIPA. While the HDI gives lip service to the need to "ensure due process for respondents," if the process by which the HDI Practices themselves were developed is any guide, we cannot trust that this would be the case. If any proof is needed of this, we only need to look at the ADRP's predecessor and namesake, the UDRP, a systemically biased process that has been used to censor domains used for legitimate purposes such as criticism, and domains that are generic English words. Extending this broken process beyond domain names themselves to cover the contents of websites would make this censorship exponentially worse.

Donuts Are Not Healthy

Special interests who seek power to control others' speech on the Internet often cloak their desires in the rhetoric of "multistakeholder" standards development. HDI's use of terms like "process of consultation," "best practices," and "network of industry partners" fits this mold. But buzzwords don't actually give legitimacy to a proposal, nor substitute for meaningful input from everyone it will affect.

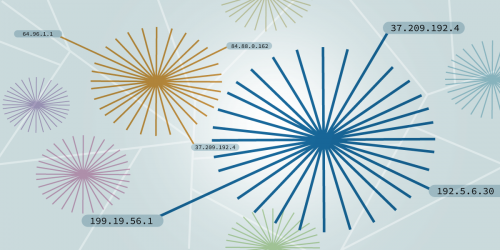

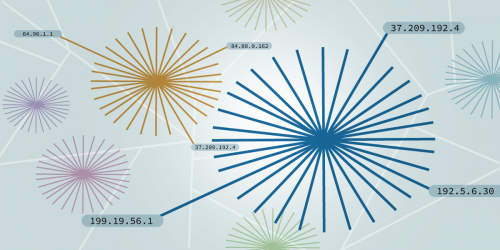

The HDI proposal was written by a group of domain name companies. They include Donuts Inc., a registry operator that controls over 200 of the new top-level domains, like .email, .guru, and .movie. Donuts has taken many steps that serve the interests of major corporate trademark and copyright holders over those of other Internet users. These include a private agreement with the Motion Picture Association of America to suspend domain names on request based on accusations of copyright infringement, and a "Domain Protected Marks List Plus" that gives brand owners the power to stop others from using common words and phrases in domain names--a degree of control that they don't get from either ICANN procedures or trademark law.

The "Healthy Practices" proposal continues that solicitude towards corporate rightsholders over other Internet users. This proposal begs the question: healthy for whom?

If past is prologue, we can expect to see heaps of praise for this proposal from the same special interests it was designed to serve, and from their allies in government who use Shadow Regulations like this one to avoid democratic accountability for unpopular, anti-user policies. But no talk of "self-regulation" nor "best practices" can transform an industry's private wishlist into legitimate governance of the Internet, or an acceptable path for other Internet companies to follow.