A Look at Copyright Enforcement Agreements

For close to 20 years, online copyright enforcement has taken place under a predictable set of legal rules, based around taking down allegedly infringing material in response to complaints from rights holders. In the United States, these rules are in Section 512 of the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA), and in Europe they are part of the E-Commerce Directive. In a nutshell, both sets of rules protect web platforms from liability for copyright infringement for material that they host, until they receive a formal notice about the claimed infringement from the copyright holder. This system is imperfect, and has resulted in many mistaken or bad faith takedowns. But as imperfect as the rules are, the fact that they are established by law at least means that they are pretty clear and well understood. That may be about to change.

Around the world, big media lobbyists are pushing for changes to the way copyright is enforced online, and they're focusing on new codes of conduct or industry agreements, rather than new laws. In particular, we have written in depth about Europe's plans to force platforms to enter into private agreements with copyright holders to filter files that users upload to the web, something that copyright holders would also like to see done in the United States. They're pushing this new upload filtering mandate through private agreements to avoid the long and divisive process of developing such requirements through laws debated in parliaments, regulations made on public record, or a balanced multi-stakeholder process.

The problem with this approach is that the more that we rely on private agreements to create a regime of content regulation, the less transparent and accountable that regime becomes. That's why EFF is highly skeptical of this backdoor approach to regulating, which we call Shadow Regulation. Copyright enforcement measures through Shadow Regulation are taking shape around the world. Here are a few examples:

- Tracking peer to peer downloads

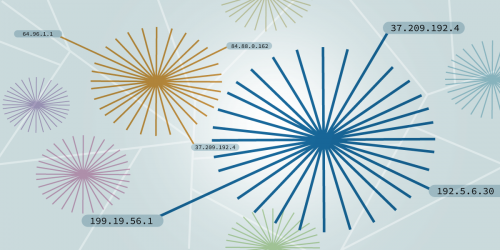

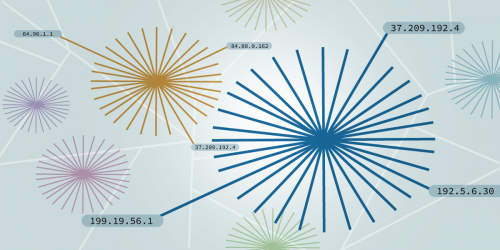

The United Kingdom is about to launch a new industry program that requires participating ISPs to deliver educational emails to users who are accused of using their connection to share copyright infringing files. This program is the UK's equivalent of the United States' Copyright Alert System, and just like that system, it subjects users to intrusive tracking of their online behavior by the private agents of copyright holders. Unlike the U.S. system, the educational emails to users will not result in any action to slow or suspend the accounts of accused users. - DNS blocking

Since 2015, Portugal has had a code of voluntary enforcement for copyright infringement that requires ISPs to institute DNS-level blocking of allegedly copyright-infringing websites. No court order is required to verify the websites put forward for blocking, which are identified by copyright associations and rubber-stamped by Portugal's General Inspection of Cultural Activities (IGAC). If this sounds a little like SOPA, you'd be right—and it's even worse because it wasn't passed by elected Portuguese lawmakers, but by a shadowy private agreement. - Privatized notice and takedown

Numerous other countries including Belgium [PDF, French], Malaysia, and South Africa, have industry codes of conduct detailing procedures for the removal of allegedly unlawful content by Internet content hosts. In some cases this includes copyrighted material, and in other cases it's reserved only for other types of unlawful content (for example, Europol’s Internet Referral Unit focuses on the voluntary removal of terrorist material). Because these removals are negotiated under a private and notionally "voluntary" agreement, they are not subject to judicial review as removals ordered by a court would be.

These agreements, and others like them, have established a bad precedent, giving a veneer of respectability to the movement in Europe to establish upload filtering system through similar "voluntary" agreements. Indeed, the more we rely on such private agreements to construct our copyright enforcement system, the more difficult it becomes to push back against further such agreements and to demand that copyright enforcement take place within a predictable, balanced, and accountable legal framework.

Copyright enforcement online is already plenty tough already, and the level of infringement that remains poses no real threat to the record profits of the movie and music industries. Therefore, there's no need for new copyright enforcement measures at all—indeed, dealing with the problems of the enforcement measures that we already have is keeping EFF busy enough.

But, the reality is that proposals for more copyright enforcement measures are already on the table in Europe, and looming in the United States. If we have to face such new copyright enforcement proposals, we would much rather do this in a forum that is inclusive, balanced and accountable than by having these proposals emerge fully-formed from an impenetrable black box, negotiated by industry insiders and lobbyists. Shadow Regulation is never an appropriate mechanism for crafting new copyright enforcement rules. If new rules ever become necessary, their only legitimacy can come from the inclusion of user representatives and other affected stakeholders at every step of the process.