Vigilant Solutions, one of the country’s largest brokers of vehicle surveillance technology, is offering a hell of a deal to law enforcement agencies in Texas: a whole suite of automated license plate reader (ALPR) equipment and access to the company’s massive databases and analytical tools—and it won’t cost the agency a dime.

Even though the technology is marketed as budget neutral, that doesn’t mean no one has to pay. Instead, Texas police fund it by gouging people who have outstanding court fines and handing Vigilant all of the data they gather on drivers for nearly unlimited commercial use.

ALPR refers to high-speed camera networks that capture license plate images, convert the plate numbers into machine-readable text, geotag and time-stamp the information, and store it all in database systems. EFF has long been concerned with this technology, because ALPRs typically capture sensitive location information on all drivers—not just criminal suspects—and, in aggregate, the information can reveal personal information, such as where you go to church, what doctors you visit, and where you sleep at night.

Vigilant is leveraging H.B. 121, a new Texas law passed in 2015 that allows officers to install credit and debit card readers in their patrol vehicles to take payment on the spot for unpaid court fines, also known as capias warrants. When the law passed, Texas legislators argued that not only would it help local government with their budgets, it would also benefit the public and police. As the bill’s sponsor, Rep. Allen Fletcher, wrote in his official statement of intent:

[T]he option of making such a payment at the time of arrest could avoid contributing to already crowded jails, save time for arresting officers, and relieve minor offenders suddenly informed of an uncollected payment when pulled over for a routine moving violation from the burden of dealing with an impounded vehicle and the potential inconvenience of finding someone to supervise a child because of an unexpected arrest.

The bill was supported by criminal justice reform groups such as the Texas Criminal Justice Coalition, but it also raised concerns by respected criminal justice blogger Scott Henson of Grits For Breakfast, who theorized that the law, combined with ALPR technology, could allow police officers to “cherry pick drivers with outstanding warrants instead of looking for current, real-time traffic violations.”

He further asked:

Are there enough departments deploying license plate readers to cause concern? Will they use them in such a fashion? How will anyone know? Is it possible to monitor—or better, measure—any shift in on-the-ground police priorities resulting from the new economic incentives created by the bill?

As it turns out, contracts between between Vigilant and Guadalupe County, the City of Orange, and the City of Kyle in Texas reveal that Henson was right to worry.

The “warrant redemption” program works like this. The agency is given no-cost license plate readers as well as free access to LEARN-NVLS, the ALPR data system Vigilant says contains more than 2.8-billion plate scans and is growing by more than 70-million scans a month. This also includes a wide variety of analytical and predictive software tools. Also, the agency is merely licensing the technology; Vigilant can take it back at any time.

The government agency in turn gives Vigilant access to information about all its outstanding court fees, which the company then turns into a hot list to feed into the free ALPR systems. As police cars patrol the city, they ping on license plates associated with the fees. The officer then pulls the driver over and offers them a devil’s bargain: get arrested, or pay the original fine with an extra 25% processing fee tacked on, all of which goes to Vigilant.1 In other words, the driver is paying Vigilant to provide the local police with the technology used to identify and then detain the driver. If the ALPR pings on a parked car, the officer can get out and leave a note to visit Vigilant’s payment website.

But Vigilant isn’t just compensated with motorists’ cash. The law enforcement agencies are also using the privacy of everyday drivers as currency.

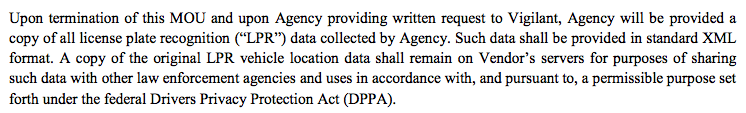

From Vigilant Solutions contract with City of Kyle

Buried in the fine print of the contract with Vigilant is a clause that says the company also get to keep a copy of all the license-plate data collected by the agency, even after the contract ends. According the company's usage and privacy policy, Vigilant “retains LPR data as long as it has commercial value.” Vigilant can sell or license that information to other law enforcement bodies and potentially use it for other purposes. (See clarification at bottom.)

In early December 2015, Vigilant issued a press release bragging that Guadalupe County had used the systems to collect on more than 4,500 warrants between April and December 2015. In January 2016, the City of Kyle signed an identical deal with Vigilant. Soon after, Guadalupe County upgraded the contract to allow Vigilant to dispatch its own contractors to collect on capias warrants.

Update: Buzzfeed has published an in-depth report on how police in Port Arthur, Texas also use Vigilant Solutions ALPR technology to collect fines.

Alarmingly, in December, Vigilant also quietly issued an apology on its website for a major error:

During the second week of December, as part of its Warrant Redemption Program, Vigilant Solutions sent several warrant notices – on behalf of our law enforcement partners – in error to citizens across the state of Texas. A technical error caused us to send warrant notices to the wrong recipients.

These types of mistakes are not acceptable and we deeply apologize to those who received the warrant correspondence in error and to our law enforcement customers.

Vigilant is right: this is not acceptable. Yet, the company has not disclosed the extent of the error, how many people were affected, how much money was collected that shouldn’t have been, and what it’s doing to inform and make it up to the people affected. Instead, the company simply stated that it had “conducted a thorough review of the incident and have implemented several internal policies.”

We’re unlikely to get answers from the government agencies who signed these contracts. To access Vigilant’s powerful online data systems, agencies agree not to disparage the company or even to talk to the press without the company’s permission:

From Vigilant Solutions LEARN-NVLS User Agreement

You shall not create, publish, distribute, or permit any written, electronically transmitted or other form of publicity material that makes reference to the LEARN LPR Database Server or this Agreement without first submitting the material to Vigilant and receiving written consent from Vigilant thereto…

You agree not to use proprietary materials or information in any manner that is disparaging. This prohibition is specifically intended to preclude you from cooperating or otherwise agreeing to allow photographs or screenshots to be taken by any member of the media without the express consent of LEARN-NVLS. You also agree not to voluntarily provide ANY information, including interviews, related to LEARN products or its services to any member of the media without the express written consent of LEARN-NVLS.

You might very well ask at this point about the legality of this scheme. Vigilant anticipated that and provided the City of Kyle with a slide titled “Can I Really Do This?” which cited a law that they believe allows for the 25% surcharge.

You might very well ask at this point about the legality of this scheme. Vigilant anticipated that and provided the City of Kyle with a slide titled “Can I Really Do This?” which cited a law that they believe allows for the 25% surcharge.

The law states that a county or municipality “may only charge a fee for the access or service if the fee is designed to recover the costs directly and reasonably incurred in providing the access or service.”

We believe that a 25% fee is not reasonable and doesn’t recover just the direct costs, since the fee is actually paying for the whole ALPR system, including surveillance capabilities unrelated to warrant redemption, such as access to the giant LEARN-NVLS database and software suite.

Beyond that, the system raises a whole host of problems:

- It turns police into debt collectors, who have to keep swiping credit cards to keep the free equipment.

- It turns police into data miners, who use the privacy of local drivers as currency.

- It not-so-subtly shifts police priorities from responding to calls and traffic violations to responding to a computer’s instructions.

- Policy makers and the public are unable to effectively evaluate the technology since the contract prohibits police from speaking honestly and openly about the program.

- The model relies on debt: there’s no incentive for criminal justice leaders to work with the community to reduce the number of capias warrants, since that could result in losing the equipment.

- People who have committed no crimes whatsoever have their driving patterns uploaded into a private system and no opportunity to control or watchdog how that data is disseminated.

There was a time where companies like Vigilant marketed ALPR technology as a way to save kidnapped children, recover stolen cars, and catch violent criminals. But as we’ve long warned, ALPRs in fact are being deployed for far more questionable practices.

The Texas public should be outraged at the terrible deals their representatives are signing with this particular surveillance contractor, and the legislature should reexamine the unintended consequences of the law they passed last year.

Update January 28, 2016: We have updated this piece to include the City of Orange's contract with Vigilant Solutions.

Clarification January 28, 2016: We originally stated that data collected under this program may be sold "potentially to private companies such as insurance firms and repossession agencies." Vigilant generally agrees in its contracts and policies that ALPR data collected by law enforcement agencies will only be shared with (i.e. sold to) other law enforcement agencies. However, data collected by Vigilant directly may be shared for a variety of purposes, including insurance and repossession. We used the word "potentially" because it gets murky when it comes to ALPR systems licensed to law enforcement that are not the property of the agency, but rather are Vigilant's property attached to a police vehicle. Vigilant's contract with the City of Kyle, for example, allows Vigilant to use the data "in accordance with, and pursuant to, a permissible purpose set forth under the federal Drivers Privacy Protection Act (DPPA)." The DPPA includes many permissible purposes, such as insurance purposes and or private investigations, but it also usually only regulates vehicle registration data, the information that would allow you to connect a name or addresses to license plates. Vigilant itself notes in its materials that DPPA regulates connecting personal information to a license plate, but argues LPR data on its own is fair game because "there is no reasonable expectation of privacy." It's also unclear how Vigilant treats data collected by Vigilant employees and contractors on behalf of law enforcement agencies, as is the case in Guadalupe County. Vigilant's policies also allow the company to retroactively change its usage rules at anytime.

- 1. The contracts are inconsistent on how this fee breaks down. For example, the City of Kyle contract lists 5% of "credit card processing," 5% for "credit card handling," and 15% for a "vendor transaction fee."