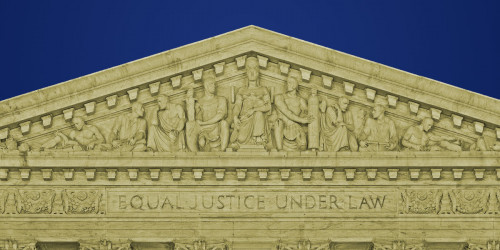

The Texas Supreme Court today ruled that orders preventing people who have been found liable for defamation from publishing further statements about the plaintiff are “prior restraints,” a remedy that the First Amendment rarely permits. Adopting a position advocated by EFF in an amicus brief, the court also delightfully quoted The Big Lebowski's Walter Sobchak: "For your information, the Supreme Court has roundly rejected prior restraint." It further rejected the argument that the ability of Internet publication to reach millions of readers almost instantaneously somehow required a change in First Amendment law.

EFF filed the amicus brief on behalf of itself and First Amendment scholars Erwin Chemerinsky and Lyrissa Barnett Lidsky urging this position, and the brief appears to have been highly influential on the court, which cited Prof. Chemerinsky’s scholarly writings extensively.

The court, in a case called Kinney v. Barnes, not only rejected the Internet-is-different argument, it took the exact opposite position, emphasizing the role of the Internet “as an equalizer of speech and a gateway to amplified political discourse.”

In ruling that post-trial injunctions are prior restraints, the court acknowledged the fundamental free speech principle that a court can prevent someone from speaking only in the most unusual circumstances. The court explained, echoing an argument made in our amicus brief, that such orders were especially inappropriate in defamation cases because a statement that it is defamatory in one context may not be in another: “Given the inherently contextual nature of defamatory speech, even the most narrowly crafted of injunctions risks enjoining protected speech because the same statement made at a different time and in a different context may no longer be actionable. Untrue statements may later become true; unprivileged statements may later become privileged.”

“The Texas Supreme Court reiterates a principle that has long been at the core of the First Amendment—that the government cannot resort to judicial orders to muzzle its citizens from speaking in the future, even if it fears their speech may be disruptive or defamatory,” said Professor Lidsky. “This principle, which prevents the permanent chilling of speech, is arguably even more important today than it was at the founding of the republic, as more citizens than ever before are communicating information, thoughts, ideas, and images to mass audiences.” Prof. Lidsky’s article on defamation in cyberspace had been cited by the plaintiff in support of its extreme position. She appeared as an amicus in this case to emphasize that her article should not be read to suggest that Internet speech should receive diminished First Amendment protection.

Tom Leatherbury and Marc Fuller of the Dallas office of Vinson & Elkins were co-counsel with EFF on the brief.