Bad facts make bad law: it’s legal cliché that is unfortunately based on reality. We saw as much yesterday, in the case of Ryan Hart v. Electronic Arts. Presented with a situation that just seemed unfair, the Third Circuit Court of Appeals proceeded to make a whole bunch of bad law that puts dollars ahead of speech.

Here are the facts: Electronic Arts sells a videogame called NCAA Football. Part of the success of the game is based on its realism and detail—including its realistic digital avatars of college players. One of those players was Ryan Hart, who played for Rutgers University from 2002 to 2005. NCAA Football did not use Hart’s name, but the game included an avatar with Hart’s Rutgers team jersey number, biographical information, and statistics. Trouble is, no one asked Hart if he wanted to be part of the game. Nor did anyone pay him for it—they couldn’t, because college players aren’t allowed to accept money for any kind of commercial activity. When Ryan discovered the game, he sued EA based on a lesser-known but pernicious legal doctrine, the right of publicity.

The right of publicity a funny offshoot of privacy law that gives a (human) person the right to limit the public use of her name, likeness and/or identity, particularly for commercial purposes like an advertisement. The original idea was that using someone's face to sell soap or gum, for example, might be embarrassing for that person and that she should have the right to prevent it. While that might makes some sense in a narrow context, states have expanded the law well beyond its original boundaries. For example, the right was once understood to be limited to name and likeness, but now it can mean just about anything that “evokes” a person’s identity, such as a phrase associated with a celebrity (like “Here’s Johnny,”) or even a robot dressed like a celebrity. And in some states, the right can now be invoked by your heirs long after you are dead and, presumably, in no position to be embarrassed by any sordid commercial associations. In other words, it’s become a money-making machine.

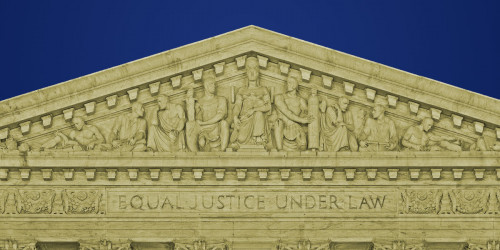

But there has traditionally been at least one limit on publicity claims: the First Amendment. In a nutshell, courts are supposed to balance a person’s right to control the use of her identity against others’ right to expressive speech – including videogames. Unfortunately, the Third Circuit just threw that balance way out of whack.

The good: The court recognizes that videogames are protected expression under the First Amendment, and that free speech is important. Whew!

The bad: The court embraced the wrong test for balancing a person's commercial interests against free speech. Many courts have sensibly borrowed from trademark law and found that, where the invocation of an identity is part of the expressive purpose, the court should not punish it unless it is in essence a disguised advertisement, e.g., the user is just trying to use a person's name to call attention to a product (like potato chips).

Here, the court went off in an entirely different direction, borrowing instead from copyright law to conclude that only uses that are “transformative” can be protected by the First Amendment. In copyright, whether a work is transformative, i.e., creates something new with a different purpose or character, is an important part of the fair use analysis. However, the court imported a decidely narrow approach to transformativeness: did not consider whether the game as a whole had transformative value, as one would in a copyright case, but focused solely only on how Hart's identity was used or transformed. The court reasoned that since the “digital Ryan Hart does what the actual Ryan Hart” did, i.e. play college football, there was no transformation and Hart’s economic interests trumped EA’s free speech interests. The court was also selective about what it chose to import from copyright, ignoring several other factors relevant to fair use, such as market harm and whether the underlying work is factual (if so, copyright protection is “thinner”).

As a group of video and filmmakers pointed out, the transformation test is a bad fit for publicity rights. The fair use analysis generally balances competing speech interests—those of the original and secondary authors. But there is no speech interest in cashing in on your fame. In addition, copyright law is designed to encourage creativity through economic incentives. No such additional incentive is needed for celebrities.

It’s entirely understandable that a court might sympathize with Ryan Hart. But if the court’s test was applied broadly, it could have a devastating impact on creative works that relate to real people and life stories. For example, the rationale would apply directly to political biographies or biopics like The Social Network. It could even impact news reporting. The appellate court’s decision sends a message to all creators—if you create a work that happens to evoke someone’s identify, and your use isn’t “transformative” enough, your free speech is less important than that person’s ability to milk his or her fame for everything it’s worth.

Finally, the ugly: The Third Circuit expressly embraced a very silly notion: that your name and fame are your “property.” Nonsense. Publicity rights are, at most, a limited right to control the use of aspects of your identity for commercial purposes—nothing more, nothing less. As we’ve seen with copyrights and trademarks, treating limited monopolies in certain expression as a "property" leads people to embrace broad and dangerous new forms of protection for that "property." By treating publicity rights as equivalent to a real property rights (in your home, for example), the court gave far too much weight to celebrities’ interest in control over their image and far too little weight to free speech.

Bad facts, bad law. We hope EA appeals this decision, and that the Supreme Court overturns it.